Images Collection

Read OCR Digitized Article Text

NOTE: This plain text article interpretation has been digitally created by OCR software to estimate the article text, to help both users and search engines find relevant article content. To read the actual article text, view or download the PDF above.

Symp. zool. Soc. Lond, (1978) No. 42, 79—88

Male Mating Strategies of Dictynid Spiders with Differing Types of Social Organization

R. R. JACKSON8

NC Mental Health Research, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

SYNOPSIS

The social organization of Mallos trivittatus and Dictyna calcarata is communal and territorial. These spiders live in web complexes which are divided into defended territories. M. gregalis lives in a communal and non-territorial social organization, in which hundreds of spiders share communal webs without territories. In the territorial species, the web itself releases courtship, and males discriminate between webs of conspecific females and those of other species and between webs of conspecific females and conspecific males. This response pattern is probably related to the relative rarity of encounters between males and females. In the non-territorial species, encounters between males and females are comparatively common, and female silk does not release courtship. Instead, the males seem to incorporate a sexual advertising routine into their activity budgets.

INTRODUCTION

Most web-building spiders, including most of the Dictynidae, tend to be solitary. Except for male/female pairs or females with their newly hatched progeny, one usually finds a single individual in each web, and webs are not connected to other webs by silk. However, there are some exceptional species, generally referred to as “social spiders” (for reviews, see Burgess, 1976; Krafft, 1970; Kullmann, 1968, 1972; Shear, 1970), in which large groups of individuals share a common web. One of these species is the dictynid M. gregalis (Simon) (Diguet, 1915; Burgess, 1976), which lives under a communal and non-territorial social organization (Jackson, 1977). In this species, hundreds of individuals of all sex and age classes tend to share a communal web on which they routinely feed in groups on the same prey items. Aggressive and cannibalistic behavior normally does not occur. Some other dictynids live in web complexes, in which they maintain a communal and territorial social organization. Web complexes consist of individual web units, connected to each other by silk and defended by the occupants. In these species aggressive and cannibalistic behavior is relatively pronounced, and it is exceptional that individuals feed in groups.

a Present address: Zoology Department, University of Canterbury, Christchurch 7, New Zealand.

80

R. R. JACKSON

In this paper, correlations between male mating strategies and the social organization of the species will be discussed. Four related questions were investigated. Does the web itself release courtship from the male? Do males discriminate between the webs of conspecific females and those of other dictynids? Do males discriminate between the webs of conspecific females and those of conspecific males? Do the answers to these questions vary with the type of social organization adopted by the species?

Combining and modifying^)» definitions of Manning (1972) and Morris (1956J, Courtship is defined as heterosexual communicatory behavior that forms the normal preliminaries to mating. The courtship behavior of three ^Ipecies, M. grega (communal, non-territorial), M. trivittatus (Banks) (communal, territorial) and Dictyna Banks

(communal, territorial), has been studied in the laborateitfl In each species, there *§-& phase of cogwjtehip during which the spiders are not in physical contact yyitli each other. The male plucks on the web with his forelegs in a species-specific manner. During the contact phase that follows, the male presses his face against the female in a species-specifkg manner, and there may be periods of stroking with his palps, biting or pushing. Species-specific patterns of abdomen twitching occurred during both phases (®P||§ry courtship interaction that has been observe^ nr each species. This behavior valuable indicator ^sexual response in IfiteSe spiders because it usually occurred exclusively dsi®|ng intraspecifis® interactions.

METHODS

Maintenance

The laboratory colonygregalis originated from spiders collected by J. W. Burgess, near Guadalajara, Mexico. These were maintained on large communal webs in the laboratory and fed ad alt house flies (Musca domestica) approximatelyy five days. M. trivittatus were collected in the Chiracahua Mountains and Dictyna calcarata were

collected near Lake Chapala in Mexico by the author. These two species were maintained one per cagf ln the laboratory; and each cage was provided with continual moisture, through a wet cotton roll connected to the cage. Continual access to adi melanogaster was pro

vided by means of a culture of flies in a glass vial connected by a plastic tube to the spider’s cage. These cages were built from 9-cm-wide transparent plastic petri dishes according to a design described earlier (Jackson, 1974). The M. gregalis used in the experiments reported here were kept in cages of this type also. One adult spider was kept in each cage, along with three to five immature spiders. Lights in the laboratory came on at 0800 and went off at 2000. Temperature was maintained at 24°C± 1°C.

DICTYNID MATING STRATEGIES

81

Testing Procedure

A test consisted of dropping the male onto an empty web and recording his behavior for 15 min. Each male was tested twice, on one day with one type of web and on the next day with another type of web. The pair of webs were built by either two different species or by males and females of the same species. There were four time slots for testing males: 0800, 0830, 0900 and 0930. Each male was assigned to a time slot and tested at this time on both days. In each series of tests for a given set of two types of webs, 20 males of a given species were tested. One-half were tested with one type of web on the first day (group A), and the other half were tested with the other type of web on the first day (group B). Since only four males could be tested over a two-day period, ten days were necessary for each series. Decisions were made randomly, using a random numbers table (Rohlf & Sokal, 1969). These decisions included selecting the spiders to be used from among those available in the laboratory, assignment of males to groups and to time slots, and selecting the particular web of each type with which to test each male. The statistical tests that were used are described by Sokal & Rohlf (1969).

Since there were 30 min between time slots, and each test lasted only 15 min, there was a 15-min period between successive tests. This time was used to prepare for the next test. Ten to fifteen minutes before the start of each test, the spider whose web was to be used was removed, and the male that was to be tested was removed from his web. To remove a spider from its web, it was prodded with a camel’s hair brush into a transfer tube. A transfer tube is a 2- to 3-cm-long strip of transparent plastic tubing, fitted with a cork at each end.

To begin a test, the lid was removed from the cage containing the web, and the transfer tube was held over the web. If the male did not drop onto the web when the corks were removed from the tube, he was gently forced out with the camel’s hair brush.

The age and sexual experience of the males were not known in most cases, since most males were collected as adults in nature, in the case of M. trivittatus and D. calcarata, or in laboratory communal webs, in the case of M. gregalis. To obtain the webs used in the experiments, spiders were placed in clean cages, one per cage. After three days, Drosophila were provided, and the webs were used seven to nine days later. All webs from females were built by virgins, two to five weeks after they reached maturity. Each of these females underwent her final molt in a laboratory cage, and they were kept isolated from males. No webs were used in more than one test, and not more than one web of a given spider was used. Also, no males were tested with more than one sequence of two webs.

For each minute of the 15-min observation period, a record was made of whether or not the male walked. The total number of minutes during which walking was seen provided an index of locomotion, 15

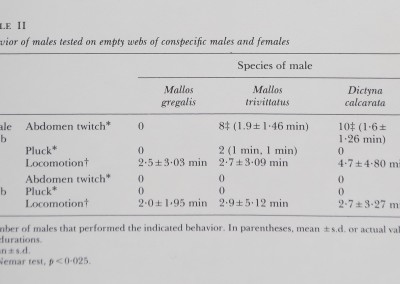

Table I

Behavior of males when tested on empty webs of females of different species

| Species of male | ||||

| Mallos gregalis | /Ifn/Inc /i/c | Dictyna calcarata | ||

| 1VJ (JLllUo LI lu ILliXlIXo | Experiment No. 1 | Experiment No. 2 | ||

| Abdomen twitch* | 0 | 7(71(2*1 ±1-46 min) | 10(9)$ (l-8± 1*87 min) | 11(7)|| (1*5± 1*04 min) |

| (Nonspecific web Pluck or spin* | 0 | 2(2) (2 min, 1 min) | 1(1) (2 min) | 3(3) (5 min,l min, 1 min) |

| Locomotion | 4-4±4-59 min | 3-4±3-69 min | 7-9±3*22 min | 6-9 ±4* 14 min |

| Contraspecific species | Mallos trivittatus | Mallos gregalis | Mallos trivittatus | Mallos gregalis |

| Abdomen twitch* | 0 | 0 | 2(1) (1 min, 1 min) | 4(0) (1*3±0*50 min) |

| Contraspecific web Pluck or spin* | 0 | 0 | 1(1) (2 min) | 1(1) (1 min) |

| Locomotiont | 3*3±3*83 min | 2-7±3-51 min | 5-6±2*50 min | 4*7±4*58 min |

* Total number of males that performed the indicated behavior. In the first set of parentheses, number of males that performed the behavior only when tested on the indicated type of web. In the second set of parentheses, mean ±s.d. or actual values for durations, t Mean ±s.d.

X McNemar test, p < 0*05.

|j McNemar test, p <0-025.

DICTYNID MATING STRATEGIES

S3

being the maximum and zero being the minimum possible value. Standing in a single location while grooming or performing elements of courtship behavior occurred at times, but locomotion also occurred during the same minute of observation in each case. In addition, indices of the durations of abdomen twitching and localized spinning were obtained by the same procedure.

RESULTS

Abdomen twitching occurred during tests with M. trivittatus and D. calearata, but npjtduring those with M. gregalis (Tables I and II). Also, four M. trivittatus males plucked onwebs, and six D. calcamt® performed localized spinning, which is another element of behavior associated with courtship in this species. During localized spinning,Ipfe male makes frequent turns as he spins in a limited area in a manner that has a more energetic andppïcited appearance than other forms df’lpinning. Each male that plucked or performed localized Ms bperformed

abdomen twitching during the same test. When abdomen twitching, plucking or localized spinning pccurred#>^^’ durations were generally brief ^Tables I and II).

M. trivittatus and • D. ca/carata discriminate between the webs of

Conspecific and Cûpteaspelptç females (^M*lelf|§hd those of females and males (Table II). I#raÉ8£eflaé trivittatus, dnly ^nSpecific female

webs released abdomen twitching. Some ft males, however,.also

performed abdomeptwitching on webs ofM. females. FdF$il|f

reason, another |#piales were tested \gith conspecific webs and webs of

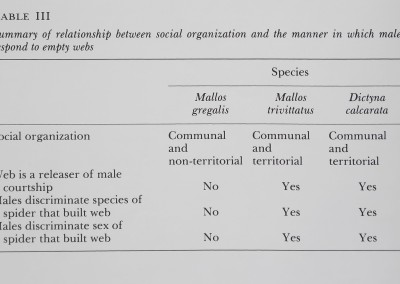

Table II

Behavior of males tested dn empty we thaïes

Species o{ male

| Mallosgregalis | Mallostrivittatus | Dictynacalearata | ||

| Female | Abdomen twitch* | 0 | $|g| ±1-46 min) | 101(1 «6 ± |

| web | Pluck* | 0 | 2(1 min, 1 min) | 1*26 min) 0 |

| Locomotiont | 2*5±3*03 min | 2*7±3*09 min | 4*7 ±4*80 min | |

| Male | Abdomen twitch* | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| web | Pluck* | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Locomotiont | 2*0± 1’95 min | 2*9=b5* 12 min | 2*7±3*27 min | |

| * Number of males that performe | d the indicated behavior. In parentheses, mean | ±s*d. or actual values | ||

for duration!, f Mean ± a,d.

t McNemar test, £< 0*025,

R. R. JACKSON

84

M. gregalis. Again contraspecific webs released abdomen twitching in a few cases. However, abdomen twitching was more often released from conspecific webs in both sets of tests. Although incidences of plucking on the web and localized spinning were infrequent and significance was not shown (McNemar tests), it is consistent that these motor patterns were seen most often on webs of conspecific females, and they were performed by communal, territorial males ofl^P. There was no indication that activity differed according to the type of web on which the male was dropped (Wilcoxon Jfcsts),

To summarize, webs released courtship from males of two communal, territorial species, tjügt not from the males of the communal, non-territorial species III). Some preliminary observations carried more casual suggest that a longer period of

observation would not significantly .âüfer these resuh%.:Males were observed for 60 tq Q® min after being placed i ndividuaHi^«n empty webs built by conspecific fff^lff^fvlone of six observed M. gregalis males initiated courtship. Of four observed M. tfivittgikis males, performed abdomen twitching Within the first 15 min, but soon plucking

was seen, and abdomen twitching occurredfirst 15 min.

Table III

Summary^mmSèmtdài brntmeeU sMÈal organization and the manage in wkiih males respond to. empty ipfe

| Species | ||

| Malim * | Dictyna | |

| grêgêiis | calcarata | |

| Social organization | Communal ï | ||

| V*4®1ÏÉ | and | and | |

| non-territorial | territorial | territorial | |

| Web is a releaser oi Mate | |||

| courtship | IMP | ¥«|9 | Yes |

| Males discriminate species ollt | |||

| spider that built j^eb | ■■ | Ye» | Yes |

| Males discriminate sex of | |||

| spider that built web | No | Yes | Yes |

DISCUSSION

The manner in which dictynid males respond to empty webs seems to be related to the type of social organization adopted by the species. In a web

DICTYNID MATING STRATEGIES

85

complex of M. trivittatus or D. calcarata,there are individual web units, each of which may or may not be occupied by a female. Also, spiders of these species are occasionally found in isolated webs, not within a complex. A hypothetical mating system will be proposed for these species. Males wander about, encountering different web units. Upon encountering silk that was recently spun by a female, the male is alerted to her possible presence, and he begins tppiiÉrt. If the female is present, she responds by walking or plucking, and the male Ctfijtinues to court. If she is not in the web, the male soon celtes t&cWrt, departs from the web unit, and continues his search, The number of females with which a male mates is probably?! d#tfiF®mnant of his reproduewte success, A limiting fector may be the-muftrber of females that a ïpÉl®* encounters. From this perspective, each encounter with a female % a^ilatively important fvent fpp* the male. Related spt-difie stimulus (female

silk) peases courtship in the

The situation i# different in M. Set and females are

continually in relatively close proximity t^puA^lher in a communal web in which there are no individual subunits analogous t# 1IM©

communal,tifirritorial species; Encounters wyjHf emales and silk laid by females must be frequent events for a male of “M. gregalis, and the that silk alone is not sufficient to .release courtship in this species would seem to be r^tatiu lb this. Putthertnore, courtship and iïïMffflÿ in trivittatus and IX cakêrata can be staged, in #>©iftain sense; ‘but only sponti»neousl^O;g«.urrinf courtship and .r®fftî’ng ‘ Were Observed in gregalis. When a male of M. trivittatustjf 0%’ÿÿmÊÊ^ -was dropped onto webs Containing a conspecific female and observed fi®Tva period ranging up ’ td loverai hours, courtship wst£ observed itt’ most cases, when dfe same types of observation were carried out with M. gregalis, courtship seen.

The number Of» fellas encountered would hffi p limiting

factor for the^yeprodutodive success males. However, the

number of|l|É0pnters îéœjlfive females rqay be important. In the

hypothetical mating s^lftn proposed gregalis the male has an

advertising routine that is structured into his activity budget, instead of courtship being released by specific stimuli. For a certain amount of time, perhaps each day, he advertises himself ;ps a male that is ready to mate. These signals are broadcast instead of being directed at particular females. Pluck-walking, a form of behavior that would seem to fit this description, is rather frequendy seen occurring spontaneously in communal webs in the laboratory. The male walks slowly, alternately plucking in the web with first one foreleg and then the other. Males pluck-walk spontaneously when they are in webs not containing females; and when in webs containing females, males that are pluck-walking are not always in the immediate vicinity of another spider.

Probably pheromones are involved in releasing courtship from males of M. trivittatus and D. calcarata that contact webs of conspecific females.

86

R. R. JACKSON

but further investigation is needed. Although sex pheromones in spiders have not received nearly the attention given this phenomenon in insects (Shorey, 1976), there is evidence of airborne sex attractants in certain web-building species in the families Araneidae (Blanke, 1973, 1975) and Dipluridae (Hickman, 1964). Crane’s (1949) studies with salticids implicated an airborne pheromone that lowers the male’s threshold for courtship in these spiders that do not build webs. In a number of species of Lycosidae, another group of vagabond spiders, when the male crosses the path of a female, he responds with searching and/or courtship behavior (Bristowe & Locket, 1926; Dondale & Hegdekar, 1973; Engelhardt, 1964; Farley & Shear, 19711; Hegdekar 8c Dondale, 1969; Hollander, Dijltstjït* Alleman It Kastos^ 1936;

Koomans, van der Ploeg 8c Dijkstra, 1974; Richly, &: van der Kraan, 1970). The dragline may or may not be neœssarjgg

and the spfcies sfeç|%ity^^ the response varies with the species involved.

Foelix (197Ü) has described hairs from the legs and palps of aranek|i spiders tha| resemble the chemosensitive hairs of insects, and we might expect bjtfe g£-tfiis type to be receptors for pheromones?”;*

In the case of and D, we do nttfeknow yet.

whether webs of mated females release courtship, since the webs of virgins were Used. Although females of these species Will mate with more than one male before the possibility that females

regulate the production of courtship-releasing pheromones associated with their si|k, in accordance with factors determining their receptivi^. In several cases whin males were placed on webs containing conspecific females that had mated ,pmeviQM,flS%ith other males, several hours passed during which the |0urtship did not occur, after which the male was removed. Although there are other potential explanation^ one possibility il that these females had shut off production ,of courts ship-releasing pheromones.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For valuable discussions and comments on the manuscript, I would like to thank P. N. Witt, R. f, Yamamoto, M, C, Vick, S. E. Smith, F. E. Enders and J. W. Burgess. Special thanks go to W. J. Gertsch for his assistance in the identification of spiders. The assistance of C. E. Griswold, P. S. Jackson and V, D. Roth in helping me locate spiders in the field is gratefully acknowledged. The assistance of the Southwestern Research Station of the American Museum of Natural History is gratefully acknowledged. Thanks go to R. Daniels for typing the manuscript. This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grant BMS 75-09915 to P. N. Witt.

DICTYNID MATING STRATEGIES

87

REFERENCES

Blanke, R. (1973). Nachweis von Pheromonen bei Netzspinnen. Naturwissen-schaften 60: 481.

Blanke, R. (1975). Untersuchungen zum Sexualverhalten von Cyrtophora cicatrosa (Stoliczka) (Araneae, Araneidae). Z. Tierpsychol. 37: 62-74.

Bristowe, W. S. & Locket, G. H. (1926). The courtship of British lycosid spiders, and its probable significance. Proc. zool. Soc. Lond. 1926: 317-347.

Burgess, J. W. (1976). Social spiders. Scient. Am. 234: 100-106.

Crane, J. (1949). Comparative biology of salticid spiders at Rancho Grande, Venezuela. Part IV. An analysis of display. Zoologica, N.Y. 34: 159-214.

Diguet, L. (1915). Nouvelles observations sur le mosquero ou nid d’araignées sociales. Bull. Soc. natn. acclim. Fr. 62: 240-249.

Dondale, C. D. 8c Hegdekar, B. M. (1973). A contact sex pheromone in Pardosa lapidicina Emerton (Araneae: Lycosidae). Can. J. Zool. 51: 400-401.

Engelhardt, W. (1964). Die mitteuropâischen Arten der Gattung Trochosa C. L. Koch 1848 (Araneae: Lycosidae). Morphologie, Chemotaxonomie, Biologie, Autôkologie. Z. Morph. Ôkol. Tiere 54: 219-392.

Farley, C. 8c Shear, W. A. (1973). Observations on the courtship behaviour of Lycosa carolinensis. Bull. Br. arachnol. Soc. 2: 153-158.

Foelix, R. F. (1970). Chemosensitive hairs of spiders. J. Morph. 132: 313-333.

Hegdekar, B. M. & Dondale, C. D. (1969). A contact sex pheromone and some response parameters in lycosid spiders. Can. J. Zool. 47: 1-4.

Hickman, V. V. (1964). On Atrax infensus sp. n. (Araneida: Dipluridae) its habits and a method of trapping the males. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 98: 107-112.

Hollander, J. den, Dijkstra, H., Alleman, H. 8c Vlijm, L. (1973). Courtship behaviour as a species barrier in the Pardosa pullata group (Araneae: Lycosidae). Tijdschr. Ent. 116: 1-22.

Jackson, R. R. (1974). Rearing methods for spiders. J. Arachnol. 2: 53-56.

Jackson, R. R. (1977). Comparative studies of Dictyna and Mallos (Araneae: Dictynidae): I. Social organization and web characteristics Revue Arachnol. 1.

Kàston, B. J. (1936). The senses involved in the courtship of some vagabond spiders. Entomologica am. 16: 97-167.

Koomans, M. J., van der Ploeg, S. W. F. 8c Dijkstra, H. (1974). Leg wave behaviour of wolf spiders of the genus Pardosa (Lycosidae, Araneae). Bull. Br. arachnol. Soc. 3: 53-61.

Krafft, B. (1970). Contribution à la biologie et à l’éthologie d’Agelena consociata Denis (Araignée sociale du Gabon). Biologia gabon. 6: 199-301.

Kullmann, E. J. (1968). Soziale Phaenomene bei Spinnen. Insectes soc. 15: 289-298.

Kullman, E. J. (1972). Evolution of social behaviour in spiders (Araneae: Eresi-dae and Theridiidae). Am. Zool. 12: 419-426.

Manning, A. (1972). An introduction to animal behaviour. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

Morris, D. J. (1956). The function and causation of courtship ceremonies. In Lyinstinct dans le comportement des animaux et de l’homme: 261–286. Grassé, P. P. (ed.). Paris: Masson et Cie.

Richter, C. J. J. 8c van der Kraan, C. (1970). Silk production in adult males of the wolf spider Pardosa amentata (Cl.) (Araneae: Lycosidae). Neth. J. Zool. 20: 392-400.