Peter Witt, 1918-1998

by Charles Reed, longtime colleague and Peter Witt’s close friend

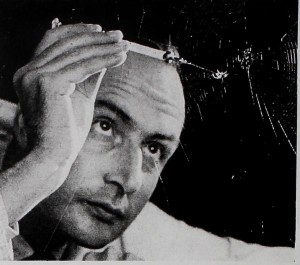

Dr. Peter Witt, LIFE magazine, 1954

In 1948, at the time of the encounter with spiders for which he is principally known, Peter Witt was an assistant in the Pharmacology Department in Tübingen, Germany. He had lived the first part of his life on the enclosed properties that his parents’ house shared with the Berlin-Grunewald villas of his maternal Mendelssohn grandparents and of his great-uncle. There began his love of gardens, music and animals that lasted all his life, and where his pride in family accomplishments matured. The Third Reich had ended all that. In 1943 he sat through a night near the burning ruins of Grunewald, guarding against looters, hearing the discord of a grand piano crashing through burning floors to the basement. Earlier, a fellow medical student, mindful that heavy explosives would follow the incendiary track laid across the city by Allied bombers, had wrestled him to shelter, pulling him from his frantic efforts to quench the already-flaming roof.

Berlin-Grunewald villas of Dr. Peter Witt’s maternal Mendelssohn grandparents

Next year, at his final medical school examination, he showed his almost impulsive readiness to rise to defend, a characteristic that was to become familiar to not a few of his later colleagues. He was contradicted when he identified loss of the patellar reflexes in tabes dorsalis as the Westphal sign. Westphal, he was told, was a Jewish professor who had arrogated what was in fact a discovery of his assistants. Nettled, Witt claimed certain knowledge to the contrary. He was very familiar with the writings of Carl Westphal, a nineteenth-century neurologist and neuroanatomist. He identified the building in which they were sitting as the site of the discovery of the Westphal sign, and Westphal as his great-grandfather. Given the institutional anti-Semitism of the time, it might have been a brash outburst of what he considered an inherited quick temper, but his examiners let the confrontation pass. Perhaps they anticipated the change that seemed on the horizon. In any case they confronted the same perplexity that officialdom had in classifying him. As he wrote in an account of those times: “I did not fit into any of the German legal definitions of “Mischling” (hybrid), in first second or third degree, nor was I “Aryan” (non-Jewish). I felt strongly that I belonged to both sides.” He had been required by this time to spend almost eight years in the labor and military services, although through much of the latter portion he was on leave at medical school in Graz and Berlin.

Apis and Peter Witt in Grimewald around 1930

On graduation, he burned his uniform and joined a physician couple, who had turned a suburban Wannsee villa into a hospital for treating victims of the bombing raids. Deserters were being summarily executed in the streets. Frequently, at a warning from his colleagues, he had to conceal himself. One day he awoke from an exhausted sleep between operations to find Russian soldiers entering the hospital. His impulsive gesture of welcome startled them in a way that, in the eyes of a coworker, looked for a moment dangerous. He remembered as one of the high points of his life these months of danger, exhaustion and service to people in desperate need. It was moreover a significant embarkation on the course he had chosen at an early age, to become, like Westphal, a practicing physician, teacher, and researcher in biology.

Sankt Georgenhof in Schwabieshe Alp

In time, the work at Wannsee became less urgent than it had been. He decided that he could join his mother and family in southern Germany, but it was not a simple matter. Life in Russian-occupied Berlin was unpredictable and sometimes threatening. Travel was restricted, and promised soon to be prohibited. His second attempt to escape and an adventurous journey brought him in late 1945 to the Schwäbische Alp, where since 1944 his mother had sheltered more than thirty family members and friends who had sought refuge in her virtually self-sufficient farm. Fresh from chaos and ruin, he was startled to find there an unreal tranquility in which he was expected to dress for dinner. “After all I had gone through, I was not prepared for the normalcy of life on the farm. I had watched the destruction of Berlin. I had dealt with people who were sick, hungry, without warm clothes and almost without hope of ever living normally again.”

Dr. Peter Witt featured in Schweizer Illustrierte Zeitung, 1955

In a matter of months Peter Witt was at Tübingen to study and write his medical doctoral thesis on chemically-induced blood abnormalities. In his later career in Switzerland and the United States he continued to investigate drugs affecting the properties of the heart muscle and the permeability of cell walls, but it was at Tübingen that he became chiefly interested in behavioral effects of drugs. Behavior had always been a strong interest, but now means for objective study seemed at hand.

After what he always described as his accidental discovery of the effects of drugs on the geometry of the orb web, a major portion of Dr. Peter Witt’s subsequent written work (over 100 papers and 3 books – like Spider Communication) was concerned with the behavior and biology of spiders and the spider web.

But before all these events he was involved in an unusual request from a branch of American military intelligence in Germany. He had just finished a series of lectures on psychotropic and addictive drugs, and a question was turned over to him: Had Adolph Hitler been over-drugged and addicted by the time of his death? At the military compound in Frankfurt, he was provided with the papers and diaries of visitors to the Berlin bunker, and the records of Hitler’s long-time personal physician Theodor Morell. Some of the observers of the last weeks were available to be interviewed. He concluded that at least one hundred drugs were administered to Hitler each day. Morell ultimately found it convenient and expeditious to deliver injections (tissue extracts, exotic suspensions and morphine) through the sleeve of Hitler’s jacket. The inquiry was terminated abruptly, without explanation. His report and notes, if they exist at all, remain in an unknown archive. His own papers contain only a letter from one of his interviewees who, in daring flights into and out of Berlin, visited the bunker in the last week of Hitler’s life. It was from the test-pilot Hanna Reitsch in a script as flamboyant as her life, writing of her disappointment that their interviews had suddenly ended.

He had inherited Swiss citizenship through his father’s father, and in 1949 he joined the Pharmacology Department in Bern. During a year at Harvard on a Rockefeller Fellowship, he crossed the country describing his work. He developed a delight in lecturing and plainly captured his audiences. When he returned to Switzerland, invitations to American universities followed him, and in 1956 he decided to accept one of them, in the Pharmacology Department in what was then the Upstate Medical Center of the State University of New York at Syracuse. As an effective teacher he had attained the third goal in his emulation of Westphal.

The decade in Syracuse brought his work to full stride. The possibility of using web geometry to identify biochemical abnormalities in the body fluids of actively psychotic people had become less likely than it had seemed at first, and his attention was drawn instead to the intricate events of web-building and to their physiological and environmental determinants. Computers were transforming research; after some initial skepticism, he found them at least useful in systematizing web measurement and description.

Dr. Peter N Witt featured in the North Carolina Leader, 1967

Peter Witt, National Geographic, 1971.

An episode at this time provides another glimpse of his value as friend and colleague. Linus Pauling was scheduled to speak at Syracuse University. Pauling had been actively voicing his opposition to atmospheric testing of nuclear devices. When he declined a university request to restrict the scope of his remarks, he was invited by the SUNY medical school to speak at its campus instead. Later the same day, a state senator expressed his passionate determination to discover who had been responsible for having the medical school’s platforms opened to what the senator considered a Communist cause. Two young members of the SUNY faculty, who had initiated the invitation, were eager to challenge the characterization and confront the controversy that seemed to be brewing. Peter Witt was foremost among those who were unwilling to have them do so alone, especially since some nervousness was apparent in their own institution. He and a few other faculty colleagues insisted on adding their names to a letter celebrating the invitation. It was a gesture he need not have made, perhaps not an impulse as hazardous as the episode with his examiners in Berlin, but of a similar nature.

Peter Witt’s last professional post might have been a culmination of his ideal course of life. Westphal, in addition to his distinguished contributions to neurology and neuroanatomy, has been credited with introducing rational and non-censorious treatment to psychiatric hospitalization in Germany.

Dr. Peter N Witt, 1964

Peter Witt was attracted to North Carolina in 1966, challenged by the new position of Director of Research in the Department of Mental Health for the state of North Carolina, and by a program that promised to invigorate research in psychiatric treatment and in the underlying medical and behavioral sciences.

His efforts in the research section led to the founding of seven independent laboratories, each directed by a prominent scientist investigating basic mechanisms of brain function and dysfunction. There he continued his own research, stimulating already-established colleagues and recruiting young assistants who on the basis of his example later found careers as scientists. And there he contributed his humane understanding to the plight of people hospitalized for psychiatric treatment, although he came to a conclusion contrary to what had become the prevailing argument that psychiatric hospitals were essentially prisons and should be replaced by treatment centers in the community. For a notably generous man, it was one of the few occasions when he failed to grant that this view shared his objective of rational and sympathetic care. Neither side welcomed the outcome: The hospitals were essentially emptied, but without providing the discharged patients with the proposed alternative treatment centers and living arrangements.

LIFE ON A THREAD GEOKNOWLEDGE, 1980

At his retirement in 1980, his was able to give his full attention to his farm, particularly to plants and the collection and breeding of animals. For over 30 years, he had risen in the very early morning to milk and walk his Nubian goats. Mouflons (large horned mountain sheep), rheas and emus (smaller relatives of the ostrich) and guanacos (relatives of the llama) roamed a large wooded and fenced area. The first of the guanacos bounded over a pen’s enclosure and disappeared shortly after it was brought to the farm. For the next week, reports of sightings came from miles around as residents of the entire county participated vicariously in the search, and actively in the triumphant return, when a cavalcade of cars followed the recovered animal and its captor up the half-mile dirt road to the house. Thereafter, when an exotic animal stranger appeared in the Knightdale countryside, it was suspected, probably correctly, to be an escapee from the Witt menagerie.

The herd of goats was expanded to supply milk for a small cheese-making business. He took special pleasure in the fact that he executed all of the processes from selection and breeding of the animals to the marketing of their produce. The scientific breeder and processor was also the empirical businessman: He had guests at the wedding party of one of his daughters rate the taste and other qualities of ten different cheeses that he had prepared for the day. The vote determined the one cheese that he would thereafter produce and sell.

Peter Witt featured in Making Cheese, 1984

L-R: Emma Witt, Peter & Inge Witt, Marie von Mendelson, baby Elise Witt. 1953

Peter Witt’s family’s love for the farm, its woods and lake, never lessened, but his strength inevitably did. A part of the farm was given away in friendship, and the rest sold. Until and even well into his last illness, time-present retained its interest and delights. One of the principal pleasures was his cello and music with his wife Inge and friends. He enjoyed characterizing and mildly ridiculing his past as one in which everyday employments were unfamiliar, almost repugnant, recalled that his mother changed a diaper for the first time when she was 61, that as a 17-year-old schoolboy he was baffled by instructions to make his bed, that he ate in a kitchen for the first time in his forties when a colleague invited him home for lunch. Though in fact he had worked in gardens since childhood, had learned shoemaking at school, and had handled horses and other animals all his life, he liked to characterize himself as a novice in a New World where he became accustomed to working with his own hands, building his own brick walls and fashioning objects like goat-milking stands out of wood. Although not naively optimistic, he celebrated things-as-they-are, resembling in this way his mother and grandmother, supervisors of grand gatherings and large properties in pre-Hitlerian Berlin, who each confessed at separate times late in their lives that the small apartments in which they found themselves were the places for which they had always yearned.

Peter Witt died in Raleigh NC, on September 15, 1998, one month short of his 80th birthday, in a beautiful house that he too came to think of as one for which he had always yearned.

A little over a year earlier, the curator of European paintings at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art was pleased to learn of the existence of what the newspaper called “a retired doctor named Peter Witt”, who was able to confirm the legitimacy of the Museum’s possession of van Gogh’s “Wheat Field with Cypress”. It had hung with other Impressionist works in his grandparents’ house and had been one of several paintings that were in his possession when he crossed from Germany to Switzerland in 1949: “I knew every brush-stroke.” The curator asked if he was “bitter” to learn that the Museum had paid a great price for the painting, and invited him to come to New York for lunch. Had the lunch occurred, the curator would certainly have discovered that the retired doctor had given up the painting with regret, but not for its monetary value, and that he was a far from bitter man. He was, in fact, that which he proclaimed to so admire in others, an “artist of life.”