Images Collection

View this article in Search Friendly Plain Text

NOTE: This plain text article interpretation has been digitally created by OCR software to estimate the article text, to help both users and search engines find relevant article content. To read the actual article text, view or download the PDF above.

SPIRALS, SPIDERS AND SPINNE RItS-

If this summer’s occupants of beach cottages and other vacation residences eyed the comers of their habitations and the nether surfaces of their furniture with more interest and respect this season, it may be attributable to Drs. Peter N. Witt and Charles E Reed. Tliese two Upstate Medical Center investigators, one a physician and pharmacologist, the other a psychologist, have made a series of studies and reports, including one in March at The Rockefeller Institute, on the ways in which spiders, particularly Arancus diadematus, fashion their webs and the effects of various manipulations on tills complex behavior pattern.

As is familiar to all who have probed die subject, even if only with an inquiring broom, there are many different types of spider webs. Most house spiders build mesh webs, irregular, fine-spun three-dimensional structures that tend to collect dust and artifacts as well as anticipated prey. These are usually maintained by colonies of spiders and are under constant repair and enlargement, sometimes attaining an Alarming size. Some spiders, usually of die out-

door variety, make sheet webs which t sails from the masts of grasses or tall llo* spread flat webs, like firemen’s nets or to catch crawling insects; and some ma funnels or tubes or pouches, each clevei to fit into cracks or to stretch between fai improbable supports. The making of ai type of web is an innate function, spec species and among all die webs. The a voritc of spider fanciers, including D: Reed, is the beautiful orb web of the coi;. spider, a’group which includes Arancus Arancus, like other orb weavers, niak several different types of dircad or silk: from about .03 to 0.1 microns in diarnc cous material for the threads is formed : glands located in the ventral portions men and extruded through spinning tub< out of the body’ in the finger-like spinner there are six in number. The spinnerets the caudal end of the abdomen. bclo\.

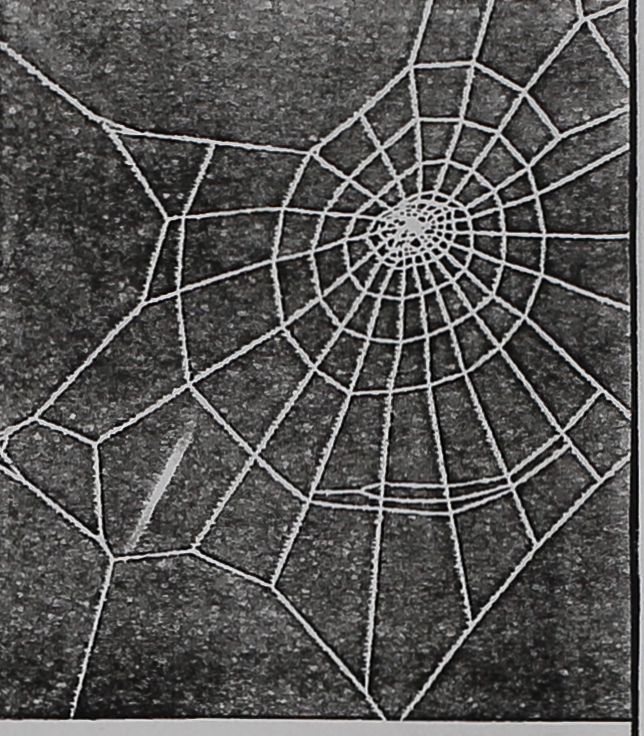

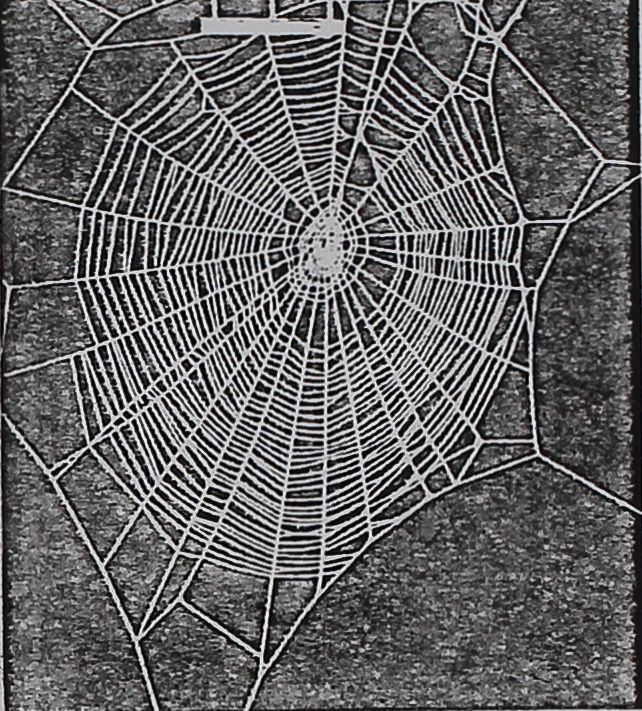

Early stage in web construction showing provisional or guy spiral which spider later replaces

punch cards. In this wray’, it is possible to store and compare data for large numbers of control and experimental wrebs and so be able to detect and pinpoint even very slight behavior changes.

To start the orb, the spider selects its center and pulls a line through it. Then the radii are fashioned, the arachnid returning each time to the hub to begin a new radius. When these are completed, a total of about 25 radii being average, Arancus then weaves a guy’ spiral, working from the hub out, to hold the radii in place. The turns of this spiral are as far apart as the spider can conveniently reach, holding out the new line at leg’s length as it crawls along the one that it has already’ just laid dowm.

When this guy spiral is completed, the spider switches to a sticky and much more elastic thread, and w’ith this w’eaves another spiral, this time working from the outside in. Just before attaching the sticky’ thread on each radius the spider gives it a little jerk with one of its hind legs so the line has a little play’ in it. This ensures that an insect that gets caught in one thread will bounce around until it becomes entangled in several others.

As the spider spins the sticky’ spiral, it cuts aw? ft

Thc Developmental Biology Discussion Group of The Rockefeller Institute was founded in 1959 by a group of faculty members and students. At first an intra-institute undertaking, it soon enlarged its scope to include sjwak-crs from other campuses and subjects other than embryology. On March 31.1964, at the invitation of Dr. Harry Meinardi and Mr. Paul Burgess, chairmen of the Group, Drs. Peter N. Witt and Charles F. Reed of the State University of New York spoke in Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Hall on “Quantitative Evaluation of Behavior Patterns: Computer Analysis of Spider Webs.” The following article is based on their presentations that evening.

The heaviest all-purpose thread of the orb-weaver is known as the dragline. It is produced constantly as the spider crawls from place to place and is fastened down at strategic intervals by “attachment discs” which actually are not discs at all but mats of minute looped threads. When a spider wants to undertake space explorations, it simply lowers itself on its dragline, which it can run right back up again if prudence so dictates.

Orb webs, according to Dr. Witt, who has been studying them for more than fifteen years, always start with a horizontal bridge. This can be produced from the dragline which the spider may cany’ the long way around from one point to another and then pull tight on arrival at its destination. In situations in which this is impossible — as in those puzzling webs that stretch across a brook — the spider raises its abdomen and spins out a line which is carried by the air currents. As soon as this line catches on a twig or leaf, the spider stops spinning, pulls it taut, and fastens it down. This bridge then can be reinforced by more dragline as the spider runs back and forth across it.

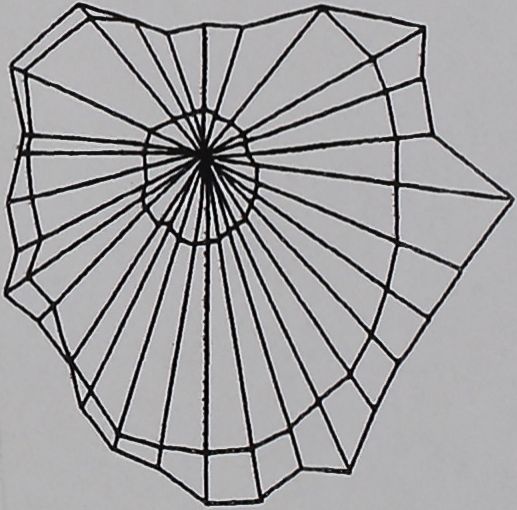

Once the spider has laid down the foundation, which is usually irregular in shape since it is dictated by the building site, construction of the orb itself begins. The orb of any species of spider is always essentially the same and is characteristic for the species. The great advantage of working with spider webs, according to Drs. Witt and Reed, apart from their intrinsic biologic interest, is that they provide a permanent record of a complex behavior pattern wliich is predictable and reproducible and can be measured in entirely objective terms.

Webs chosen for study by the investigators are first sprayed with white paint and then photographed against a black background. With the photograph enlarged to life-size, the various segments and angles of the wreb are measured and, by a method worked out by Dr. Reed, the figures committed to IBM

the guy lines and then, on finally reaching, the center, I cats the bundle of threads that have accumulated in ithe hub. Then, with its web all tidied up and ready for business, one species of spider, Zilla x-nntata, runs out of the web along one of the radii that it selects as its-guideline. This guideline vibrates when anything comes near the web and so keeps the spider in close touch with events throughout the whole structure. When Dr. Witt wants to catch a Zi7/ti-spider, he says, he throws a fly into the center of the web and while the spider is enjoying this bounty, he carefully detaches the guide wire and runs it into the bottom of a paper bag. When the spider is finished, it runs back along its line right into tlie waiting receptacle. Most spiders do not see very well, but electrical responses to flickering light in the eye of the wolf spider were the subject of some interesting studies by Dr. Robert DeVoe while a Fellow at the Institute in 1956-61. Dr. DeVoe is now at the Hopkins.

Drs. Witt aVid Reed are among the few biologists who have studied orb-weavers in the laboratoiy. The}* confine them in aluminum frames with glass walls and supply them with houseflies twice a week. Under these conditions, spiders will make a new

web almost every day, although a housefly feast mav turn off the web-building instinct for a day or two. Webs are built at tbe coldest point in the diurnal cvcle; in Dri Witt’s laboratory this is just before 5:30 a.in. when the lights and heat are turned on. The entire process takes a remarkable twenty to thirty minutes.

No step in web building is learned behavior. Babv spiders make baby webs which were thought at one time to afford them the necessary’ practice for large ones, but Russian investigators have found that if a spider is kept in solitary’ confinement from egg to adulthood and never permitted to spin even a line, it can, upon its release, make a perfect adult-sized web on the first attempt. There are a few variables. For example, the}’ have found a spider seems to plan its web on the basis of the amount of silk available for manufacturing purposes. During lean periods, when protein is in short supply, the spider will economize, making the web smaller and the threads finer; after a force-feeding of physostigmine, which increases silk secretion, larger webs are built. Heavier spiders build heavier webs, and if a tiny piece of lead is stuck onto a spider, it will make a web with

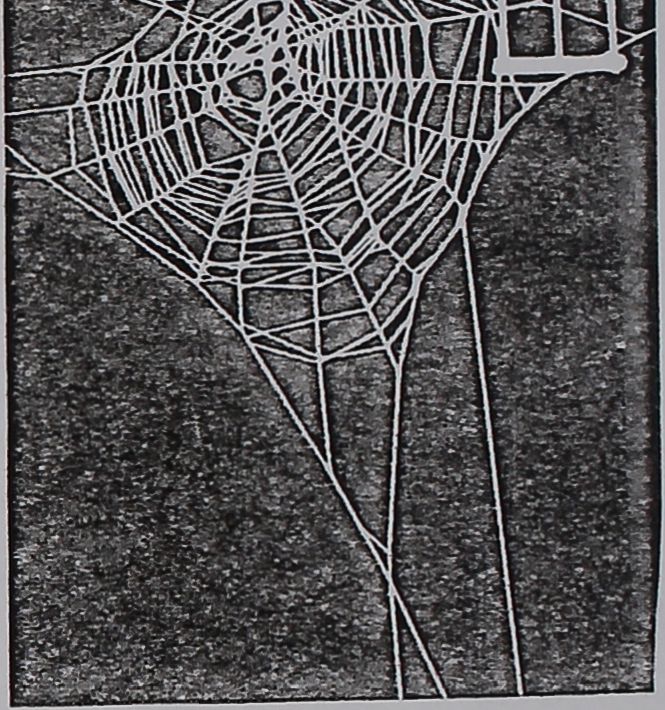

Filial stage in web construction showing sticky spiral left and web of same spider right following laser lesion

Spiders < )l liistorv and legen» lli.nc given aid to man. rwn as Aranrns dia-tlcinultis today. M.i In hoi–l s III»- was saxed mi bis lliglif horn Mecca Itrcaiist’ ;iil’an iirb\\-ox’cn across tin* ininilli bfliis caw 11i.»l It-tl his imiiriitniiiolilaical piiiMii-iN. tlie Korcisliitcs. to pass l»v liis hiding place. Itoltcrl Bruce, who failed’.six times !•» regain tin- khigdjrtni ol Scotland. watched .1 spider six (iiiics fail in attempts to fix its well In tlie ceiling and vmved l*> follow its example. Tlie spider ol course tiird again and this time succeeded wliere-iiI>»n lintel* l«-lt tlie island ol Batlilin and tank Turnlictrv (.’astlc ill tri-iiinpli Frederick I In (neat. in the first reeordeil pharmacological use of an anu linid (so named lor Araeliue ul l.vtlia.wlio made the mistake of lM*atiug Athene at a wi *a vi 1 ig qi mit *st and was turned into a spider), nliserved one fall’ into his’hot chocolate. lie called lor a fresh cup and the next moment, Irmii the kitchen, heard the rc|Mirt ol a pistol, liis cook had lx*cu hriliccl to poison him aud;‘sMp|iosiug that his tn*aeherv hail In-cii disi-overetl. 111111-iiiittial suicide I’orllivvith. It is difficult to imagine one ol Dr. Wilt’s spiders failing six times to establish its dragline or lowering itsell into a n Ifee cup. hut just as phanuaeiilogv has come a long wav in tin* past lew decades. |M*rhaps spiders have. too.

a heavier thread and. to coimieiisatc. will reduce the iiiiiiiImt of radii and spiral torus.

Weh weaving ohviuuslv icmiiies the Mlinnlh. coordinated I unit ion ol a number ol different svstems. Disturbances in .111} ol these cause «listmet. and whal iS lni»st im|Mirlaut. regularlv repeated changes in. tin; web pat tern ol the indix iilual. For example, in oik* pathlindiug experiment. a foreleg was rrmnvcijt limn each ol a group ol sixteen spiders and the welts th<*\ priKlueed wen- Miltsi*i|iieiitlv aiialv/i’d In computer and compand to conliol welts. All ol the welts maile«mi* spuler lollb^Tiig tin* amputation >Vcre the su.iiii*;, no subseipient adjust meuts were maclc*1«»r 11ic^iuix^T11 all the xyeltsdmilt. liv the S»*vendygg»-d|>|)idi-rs. the angles between t.he?i;a«lii “»Ti* 1 uglily irregular. Siunc ul the wvli.s lia«l’‘iricgii-lar ‘ptials. \\ bile smiih iIkI not anil all vvfen* the sacrii?. ov«^igaflPsha|ti* as the eontrol xvi-bs. So tlie UivestigU^ tors conclude. the Iroiitilcg is csSimtial lot the iiie.is-lulli^M.%^tlliilf iiifejiji: then* are alternate lurch* WiTisuis’lor iiu-a^ti^fig spiral lornsx and \yi*h .shape i> ilet»^!!»uu»ul liv a lot.illx m»I» ju udctil system.

M»»*ffuntl\. tlu: iuiesiigators liavv been risii adliser to piodtii» ininnt« li->ioiis. each a li.tclioii ol a Uiflli-metei in diameter, in the cephalotborax ol the spider. I.^t>l.itict’.ili^ng<j> li.iv«. been ohscKxad mjj tli»* l,l».mlw!l¥i^»tu ins III; spiilers with these* small auras

nl hraiu damage and il is IxiiVvrd that these changes’, recant la-al and analyzed, will lie a useful gaiiale In chawing a lainctmnal mail.ail ilia* relatively huge* ami alniaisl uncharted ci’iilral iii*rvt>ns »vsta-in 11I ||m* >|)i(|i-|-. •

|)iing>* dial affect ilia* ceniral nervous man alsi’i have a-lli-il.s (iii\yi-h eamslrnctinn which, according In Dr. Witt, are lar mure subtle. sensitive aiial ivpriHhicililc lhaii. Inr example*. tin* alterations iii lli«- l>raiiii\yayi\s a>1 tlK^cat. I’nr ii’islaricy.iiie>i”,ihiic Äl |)Nilai( \ hm Iintli, alli’il dii*’SpieliTs “‘jaielgi.ieilt” ill aa’ga|’il tn tfi«?, We’lglif a if flita^ifj^ that siiinitl lie ii.m’iI fair its wati ci»i^sti’Viclian 1. \ii-sealini* anal |>a nlei-dirarliil.il seem Iii inter! ere with miilor lW’fnö’ior: spiders 1.H1 di«>aj ahwlffl lir.ikc Wa*h> tli.ili are smaller iiiiall|^s^n^;gViiai’ iiTOia1nJfb.iiTcl.1u11, ()n the olliaT hand; spicleiN (akin” i lilniproiiia/iiia- i»r psilucvliili m.ika* i’iiui|)li’(i*h r«*«i»il.ir wi’li.s as lnug.;is lha*\ m.ika* waihs I’ut. \\ Iit*n llre* ajalSe- ■ re;aY?he*s^); 1 i’i‘i(tiiiri(^^ ’I*ijj;• -ii’livfioMfii^Tag

(laynftAgii; 1 >i.<.arid; Iteeil Ikdievc that tin n.h weavers ii^’|i?iT^!) in \aiiiama|cn’iia£> w ill perlians–mmieflux -n^v iaIfirn f 1 af cril^^wfM11 11 r(-a)ii;!i11 111.11 ailugimd dints in yi 1; 111. ‘jTicic is mu’.iilv gei.ieriili agreea iu.-mI that l.liev eimlal lititjjlaxe .1 iiimii* ilimjent mi talented laliMialair\ assistant dial 1 mntii*.H