Warning: Trying to access array offset on value of type null in /home/elisew5/public_html/drpeterwitt.com/wp-content/plugins/contextual-related-posts/includes/content.php on line 49

Images Collection

View this article in Search Friendly Plain Text

NOTE: This plain text article interpretation has been digitally created by OCR software to estimate the article text, to help both users and search engines find relevant article content. To read the actual article text, view or download the PDF above.

ff nni’toi3.

The Encyclopedia of the

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES

WEB BUILDING

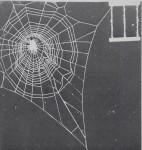

The origin of web building is seen either in the trailing drag-lines of primitive spiders or in the building of egg cocoons. As a next step silk-lined tubes with diverging threads at the entrance constitute first traps. The number of threads is then further increased to form a sheet leading to the tube. The sheet can possess a superstructure of tangled threads causing insects to fall. ,£By a process of simplification, sheet developed into orbjf, the latter covering a comparatively large area with little silk. Building of two-dimensional orb-webs has been studied extensively while influences which govern construction of other spider-webs (irregular or three dimensional, sheet, funnel, triangular webs or combinations thereof) and their sequence of construction are practically unexplored. Different types of orbs are: complete orbs (e.g. Araneus diadematus), asymmetric orbs (e.g. Mete-peira labyrinthea) orbs without hubs (e.g. Theri-diosoma gemmosum), orbs with free sector (e.g. Zilla-x-notata), and orbs with hackled bands or stabilimentum (e.g. Argiope aurantia). All these are built in the same phasic sequence. Web-building is an innate pattern of behavior which is executed by a spider in a species specific manner almost daily throughout its life; the preferred web-building time is early in the morning before sunrise. The main purpose of web-building is to

trap animals for food. The behavior pattern is considered innate because it is executed independently of learning. In evidence it was observed that young spiders built their first webs in final form without ever having seen another individual’s web, and the web changed with age independent of routine; e.g. the free sector of a Zilla web is built only in later life and is preceded by full orbs. When Zilla was kept from building webs until adulthood, it immediately constructed a free sector. Webbuilding is best understood if it is realized that spiders let out a thread wherever they run. Phases of web-building are (for names of parts see halfschematic figure of unfinished Zilla-web): Phase I: construction of a bridge connecting two points horizontally. A bridge can be built by letting a thread drift freely until it catches a branch and then pulling it straight, or in stretching a thread straight across-two arms of an angle. A Y-structure is achieved by the spider’s letting itself drop vertically from the middle of the bridge. Phase II: Each radius is built together with a frame thread or auxiliary frame thread as a Y. All radii meet in almost one point in the closely knit hub area. Phase III: Wide turns are constructed from the hub towards the periphery as temporary fixation (provisional spiral). Phase IV: The fine thread of the catching spiral is built by the spider, working inwards from the frame and running in loops or full circles towards the free zone which surrounds the hub. Simultaneously, the provisional spiral is eliminated. Phase V: The spider eats the white bundle of threads in the hub. It now settles down, keeping in touch with the completed web via radii or signal’ thread. Only the shape of the frame depends on the surroundings. Frequency of webbuilding and size of catching area are determined by outside stimuli, e.g. length of day, humidity, barometric pressure, abundance of food, and inner factors such as hunger, age, and sex. Temperature minimum before sunrise is known to be among stimuli releasing web-building in predisposed spiders. Interference experiments have shown that animals try to complete one phase before they proceed to the next, e.g. up to 150% of radii were built if some were destroyed during construction until this phase was finally exhausted, whereupon construction of a spiral was started on an incomplete basic structure. A sense of gravity regulates the relationship between the horizontal and vertical diameters of a web; e.g. turning an oval web 90° during its construction results in the building of an added area which re-establishes the diameters in the originally planned ratio. Blinded animals have built normal webs, hence vision seems unimportant in web construction. The following procedures have been described as ancillary techniques which spiders utilize during web building: probing for empty spaces, turning their bodies, pulling threads to measure tension or vibration frequency, estimating distances by spreading their legs or running a definite number of steps, and dropping the perpendicular onto a thread to establish the shortest distance. Material for web-silk is a sclero-protein which is secreted into and stored in glands

in viscous liquid form. It hardens by mechanical stretching when drawn out of the spinnerets. Threads are simple or composite, of extraordinary strength and elasticity, and between 0.03 and 0.1 micron thick. Radii and frame threads come from the aciniform and ampullate glands and are thicker and less elastic than the spiral threads. Attachment discs (composed of a large number of minute loops) are produced by pyriform glands. The spiral thread is coated with sticky fluid from aggregate glands. It is pulled out slowly by the fourth pair of legs and released with a jerk which results in formation of sticky globules along the spiral. Silk-glands are transformed coxal glands which fill a large part of an orb-weaver’s abdomen. Spinnerets are vestiges of ancestral abdominal limbs of the fourth and fifth abdominal somites.

Peter N. Witt

References: Gertsch, W. J., “American spiders”, New York, 1949; Savory, T. H., “The spider’s web”, London, 1952; Tilquin, A., “La toile géométrique des araignées”, Paris, 1942; Wiehle, W. J., in “Die Tierwelt Deutschlands” vol. 23, Jena, 1931; Witt, P. N., “Die Wirkung von Substanzen auf den Netzbau der Spinne als biologischer Test”. Berlin, 1956.