Images Collection

View this article in Search Friendly Plain Text

NOTE: This plain text article interpretation has been digitally created by OCR software to estimate the article text, to help both users and search engines find relevant article content. To read the actual article text, view or download the PDF above.

AUGUST 1971

ii|QVg|¡QH

¡ ;^BffiNWun!8

Abo|É Spiders ?

ZAHL, Phí|¡l

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SENIOR SCIENTIST

Spiders do N^ftNTiMiD^rf^ffl

Willis J. Gertsch. When I visited him

Kin his studio-laboratory at thUfoot of

the Chiricahua Mountains in south-

eastern Arizona, he dumped a live tarantula

from a glass jar onto the top of his deik. The

gray-brown, eight-legged – shaggy thinglS

neaffl|i theft^f^ of my fist—was clearly the

. stuff of which bad dreams are

“Biurihg É^pétirhe p|tfi\Si^^fc|‘eflected

pSAlhg and

resfiÉ»hg®||l? afestíéss creature, “I’ve beert

bitten by tarantulas of a dozen different

s’M^i^irAn|das Su ts’ee. and in

m«^rate|i|good healtbJa|

The big furry spider prowled iimuisitively

ÄrossHeMjäck of fias hand. “Regardless of

cfctlSued, “A taranfula bite is hardly worse

than 1> bee or wasp sting, unless you happen

fo»|ts|| a particular allergy. As a matter of

fact, some ants, bees, and wasps are far more

dangerous. But it’s the spiders that always

make the headlines.”

Dr. Gertsch had a point. Spiders are among

the most feared and maligned of nature’s

‘ among the mail] fas-■

cinating. An incredible number of species in- j

habit the world, but only a dozen or so can be

dangerous to man. And, on the other face of

the coin, nearly all do their part in keeping in-

calculable hordes of harmful insects in check.

Wind Wafts Spiders Far Out to Sea

One finds spiders almost everywhere—four

milesjH in the Himalayas, in below-sea-level

deserts, in ^^yÍMk§éÍíí8|Bmd burrowed

||feto He édipiKp Mariners fijave even sighted

them far at sea, drifting on th&wijhd, suspend-

ed from ‘fhrea#ik^“parachutes.”

TIM í averaéeMÉ&®f a »der spans only a

year, yet ,a taráfñ|ula may live as long as three

dec4§es,^Stake eight to ten years to mature.

Most spiders lead solitary lives, but a few are

social, with many individuals sharing a com-

mon web. Some species are as small as pin-

heads, others the size of dinner plates. Though

many people think of spiders as insects, they

are more closely related to ticks, scorpions,

and, remotely, to horseshoe crabs.

But chief among the marvels of the spider

is its mastery cif ;Änning.:^have watched 1

Spurred by hunger and guided by instinct, a garden spider wraps a grasshopper

in a shroud of silk. The efficient predator has killed the insect w|m a bite and now

will dine on its juices. Spiders have changed little from their ancestors of hundreds

of millions of years ago; they differ from insects in that they possess eight legs

instead of six, and have neither compound eyes nor antennae. Essential to the bal-

ance of nature, the world’s spiders—averaging at least 50,000 per acre in green areas

—annually destroy a hundred times their number in insects. Scientists have named

more than 30,000 species and estimate that four times that many remain unclassified; 1

human lacemakers work a spider-web motif

into handkerchiefs, napkins, and tablecloths,

but the result is clumsy compared to nature’s

often exquisite products.

Oddly enough, though, Greek mythology

attributes the spider’s skill to human origins.

An artful weaver named Arachne impudently

challenged the goddess Athena to a contest.

Later, shamed and mortified by her own con-

ceit, Arachne hanged herself. The goddess, in

a moment of compassion, brought Arachne

back to life, transformed her into a spider,

and made her noose into a web.

“Live,” Athena commanded, .. and that

you may preserve the memory of this lesson,

continue ho hang, both you and your descend-

ants»»! future times.” And so the name of

that superb; classical spinstress has been per-

petuated by scientists: Arachnologists like Dr.

Gertscm stfiply jthe class Arachnida and the

order Araneida—spiders as a group.

Dr. Gertsch ami^^y’ jboaxed his eight-

lagged friend, back into; its jar. tif¡ scLJ

entist, retired after many years as curator of 1

spiders at the American Museum of- Natural \

History in New York City, gave me a quick

refresher course on arachnid evolution.

“Spiders’ bodies and habits have become

adapted to harvesting insect food supplies in

a multitude of habitats. Most hunting spiders

prowl on the ground, relyihg mainly on 1

strength. Keen-sighted wolf spiders and j ump-

ers use sheer speed in overtaking prey. Aerial

“í^lurderous biting robber”: The translation of the

black widow’s scientific name, Latrodectus madam,

attests to the infamy of the little weaver (above). This

most dangerous of spiders usually bears a red hourglass

marking on its underside (left). One of about a dozen

species that need be feared by man, it occurs commonly

throughout mijst of the United States.

||®1he Pack widow’s venom—more potent drop for

drop than a rattlesnake’s—causes intense pain. Deaths,

however, occur from only four or five of the more than

.1,000; bites reported in the U- S. each year.

Only the female black widow causes human fatali-

¡*É@s. ßlptrary to the belief that gave her the name, she

4 does not always kill the much smaller male after mat-

ing. If hungry, however, the widow, like the females of

most spiders, will resort to eating her own kind.

As the body juices are

sucked up, lobe hairs filter

out spUd particles.

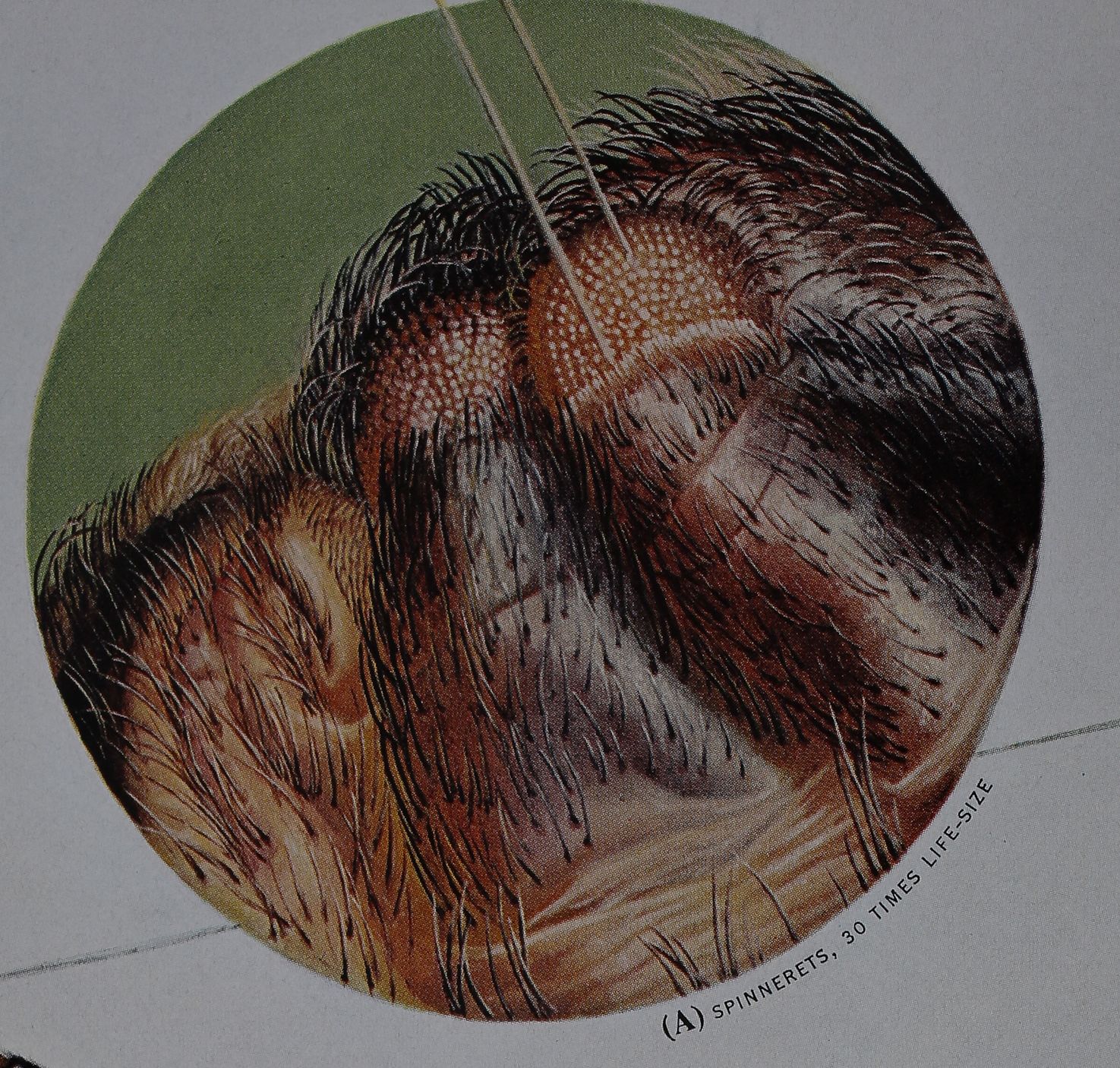

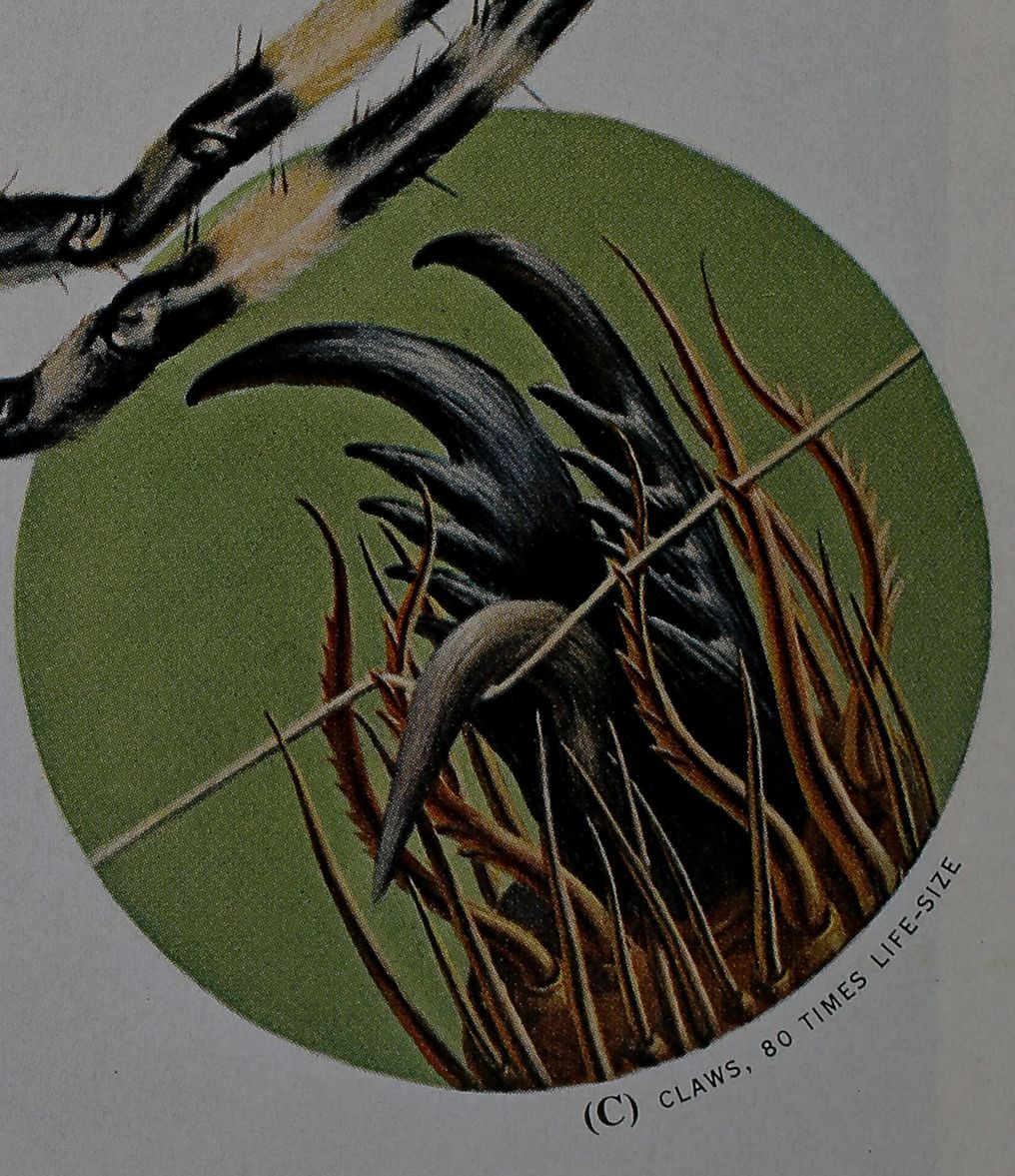

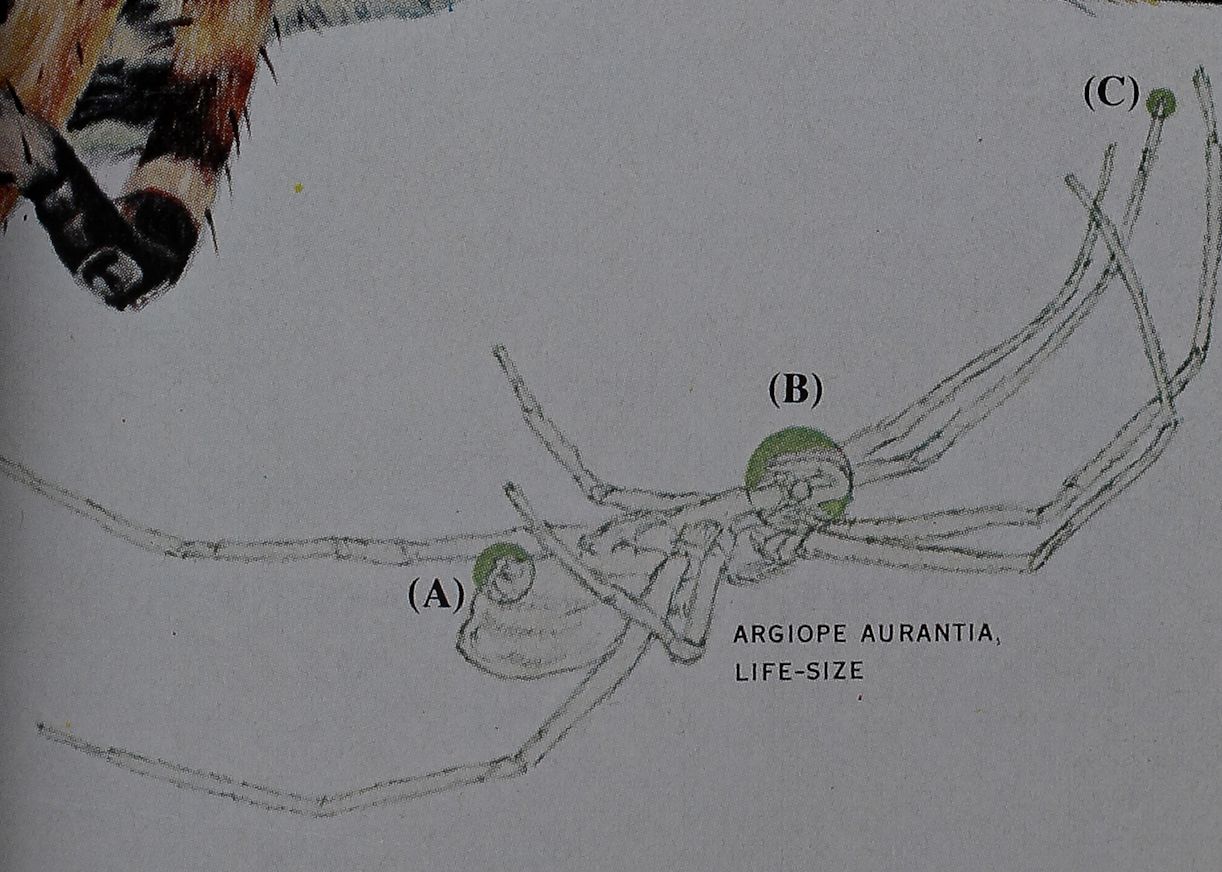

Curved claws and thick

barbed hairs at the tip of

each leg (inset C) permit

orb-web spiders to race

across silken lines. They

avoid entanglement in

their own snares by walking

only on the dry radial

strands and shunning the

sticky spiral threads.

The spider tugs thread

from the spinnerets by

snagging it with the saw-

tooth hairs and gripping

with the bent median

clawt The faster silk is

drawn from the body, the

stronger it becomes.

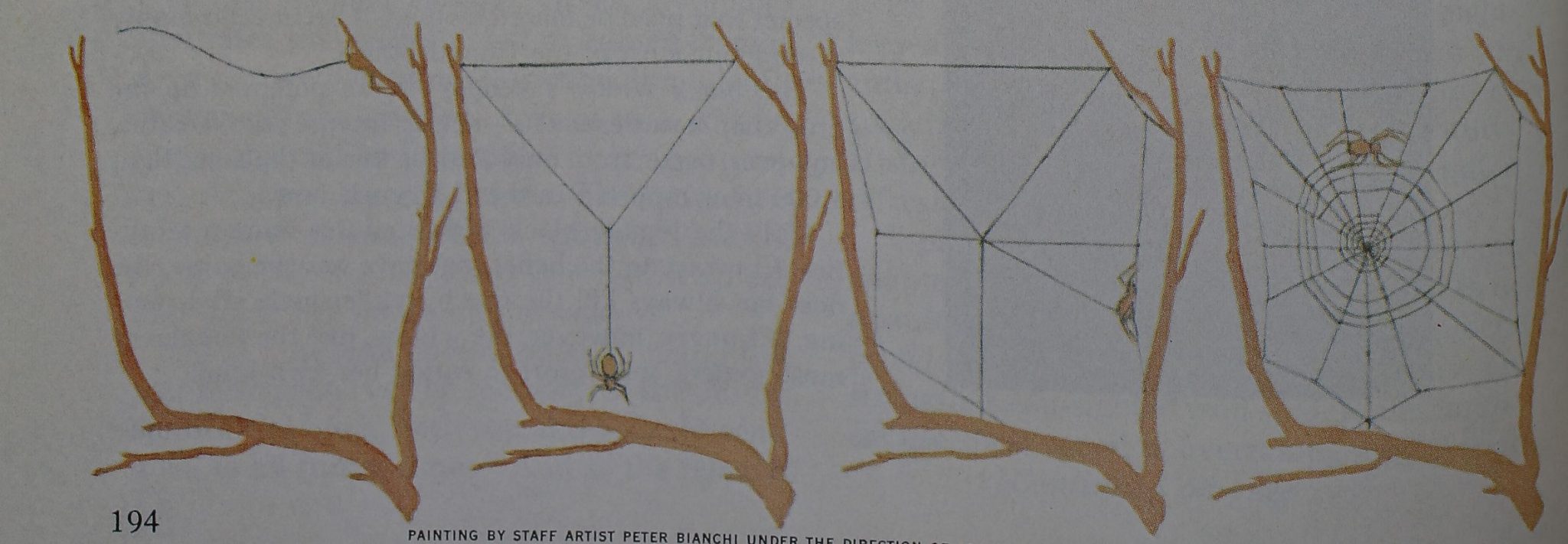

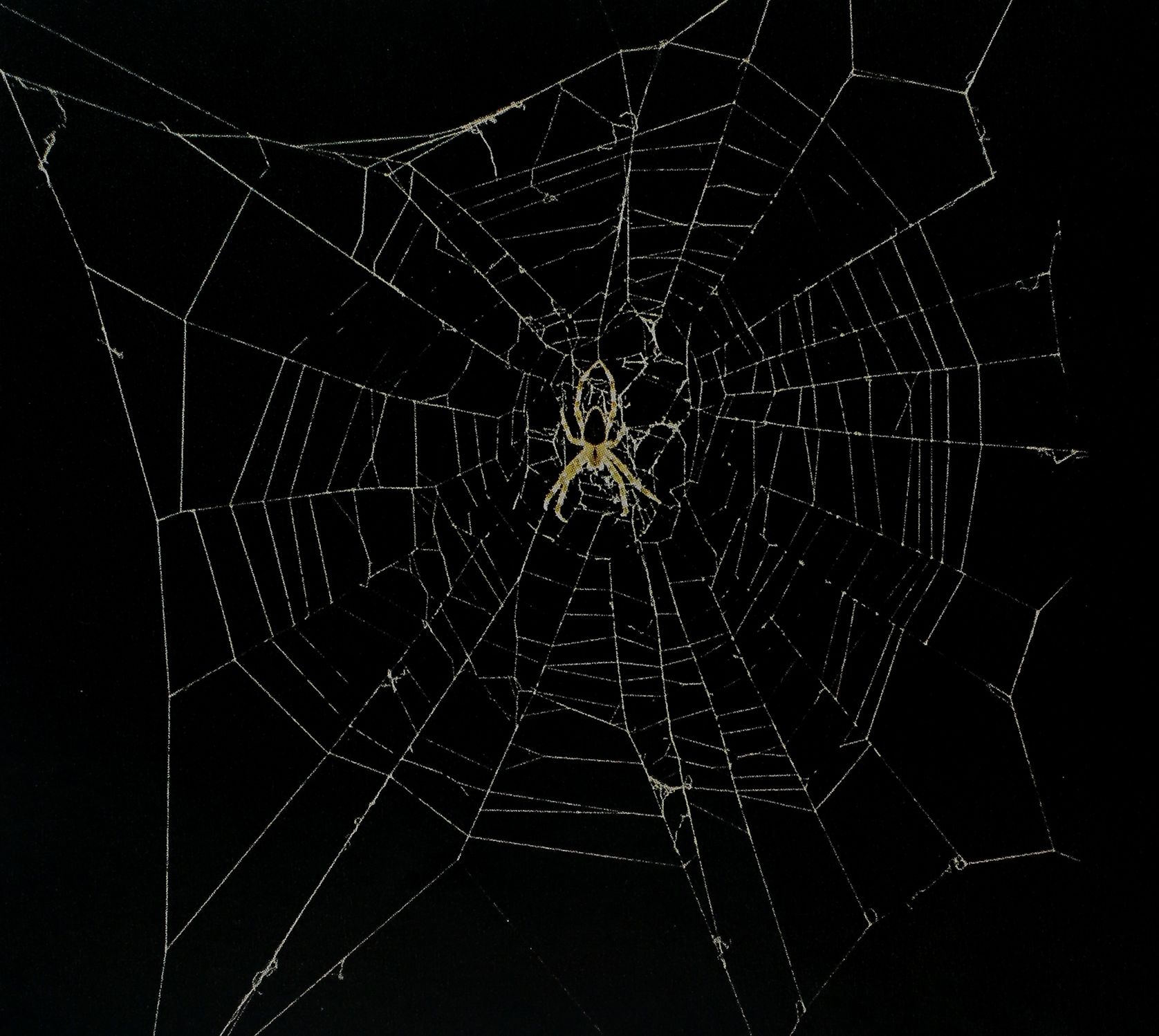

An orb weaver uses the

wind to set the bridge line

of its home (far left).

Dropping from the center

of a second strand

stretched across the gap,

it anchors a vertical thread

and quickly secures more

radial lines. Then, starting

from the hub, it puts down

a temporary dry-thread

spiral. That done, it

reverses direction and lays

down a new one of sticky

insect-trapping silk, while

rolling up the first spiral.

clear

¡I. a I OaEE1 M l^^|aS‘yiS

.;^^ñ?TOu^lv3\\ ait in

their webs for dinner to arrive, the ogre-faced

¿rtM¡ju jÄbvBne^KQflH

and flings the snare whenever an unsuspecting

name is

vi^jjl’c in |jM;s {laMKigr.anh.

argiofh: (below) rests head downward at the

hub of«r lyfetrly three-imt^d^jjftiiiT^^Bmi

er

adorns the ¿rife

tJBece

tion remains a mystery.

gS^t^awb’KxjmoHag dew, an orb wel^i’jÉW

rM|ls’ the beau t\ mfflrefe^sti@anchM¿y¿Ppf|

Goliath among spiders, an Ameri-

can tarantula calmly submits to a

close-up inspection by Arizona col-

lector Lorin Honetschlager and his

daughter Julie.

New World tarantulas—unrelated

to Europe’s Lycosa tarentula—retain

features of the most primitive spiders:

four lungs, jaws that move vertically

instead of horizontally, and minimal

use of silk. Some have legs spanning

nearly ten inches, making them the

world’s largest spiders. Despite their

formidable appearance, American

tarantulas pose no danger to man.

spiders have devised three-dimensional webs

within which they hang upside down (page

219), mazes of lines to entrap crawling insects,

and sheets and aerial tangles to intercept

jumping insects. And the orb weavers spin

round geometrical webs that efficiently en-

tangle flying or jumping insects.”

Dr. Gertsch’s own favorites are the more

primitive spiders: American tarantulas, trap-

door spiders, purse-web spiders, and the most

primitive of all, the liphistiids, little changed

since Carboniferous times, some 340,000,000

years ago.

Walking Factories Produce Varied Silks

In my own exploration of the spider world,

I found myself endlessly fascinated by the

orb weavers. The raw material of their gossa-

mer creations—a complex protein substance

—is manufactured by five or six spedH

glands in the spider’s abdomen, each pro-

ducing its own variety of silk. Acting sepa-

rately or in combination, these glands supply

dry or sticky threads for lines, cables, and

attachment disks for webs; egg sacs; anchor

lines; and swathing bands to bind prey.

The precise form of the filaments is deter-

mined by spinnerets—clusters of tiny nozzled

jets from which the spider draws the silk

with its hindmost pair of legs. The resulting

strands of spider silk are incredibly elastic

and tough—some can stretch more than 20

percent and are stronger than steel wire of

the same diameter!

For all its beauty and dewy sparkle, the

spider web is a diabolical achievement. To

be sure, heavy insects like beetles and wasps,

blundering into the snare, are apt to rip

right through. But for lighter prey, the sticky,

almost invisible network means death.

When delicate touch receptors pick up the

slightest impact of an insect on the web,

the spidef skims across it to paralyze the

victim with a single bite and binds it with

silk (page 191). The hapless insect will either

be eaten summarily—the body sucked dry of

its nutritious fluids, the remains discarded—

or left hanging in its mummylike wrapping

for a future meal. In his classic work The Life

of the Spider, J. Henri Fabre puts words into

the mouth of a simple garden spider, “We

must eat to have silk,” the spider exclaims,

K‘,we>mullfrhÉve sifÉ to,’ eat..:

Instinct alone controls the weaving. But al-

ter ever so slightly the spider’s internal chem-

istry, and the web will show it. I saw this

demonstrated one morning in the laboratories

of North Carolina’s Department of Mental

Health, which experiments with spiders in

one phase of a search for diagnostic clues to

various mental illnesses (pages 200-201).

Within an aluminum frame an orb weaver

was performing a sequence of rapid runs, j

ascents, and descents. Tattered remnants of

an earlier web stuck to one edge of the frame.

“Every morning we make her spin a new

web,” said Mrs. Mabel Scarboro, a research ■

assistant. “In the wild, a web seldom lasts

more than a day or so; it’s ripped by wind, or

insects, or even the movement of the spider

itself. Even though we feed this one, her in-

stinct tells her to keep her web in good repair

or she’ll starve.”

In half an hour a completed web filled the

frame. It was a circular marvel of straight

lines, angles, and more than 800 individual

; Cautious ‘but eager .té

■mission! in life—mating—a mJ^ta-

I rantula warily approaches the attack-

> ready female at extreme right Leglike

I palpi carry sperm, transfe^

pore ||£ his

He advances »y|i|h spurred forelegs

■poised. The fe«¡¡lé|§ii^

I legs, raising awésóme fangs- to, deliver

t a deatlwdealhglfh^

I can|^|ke,^fe’ mate*s

■ up, catching the fangs.,with Ids spurs.

I Thus protected, he forces her pipward^

I exposing a furrow on her abWomen in

I wkir.h .he.;A^.O^

Kpi¿ií-iiic*l’dW). ’

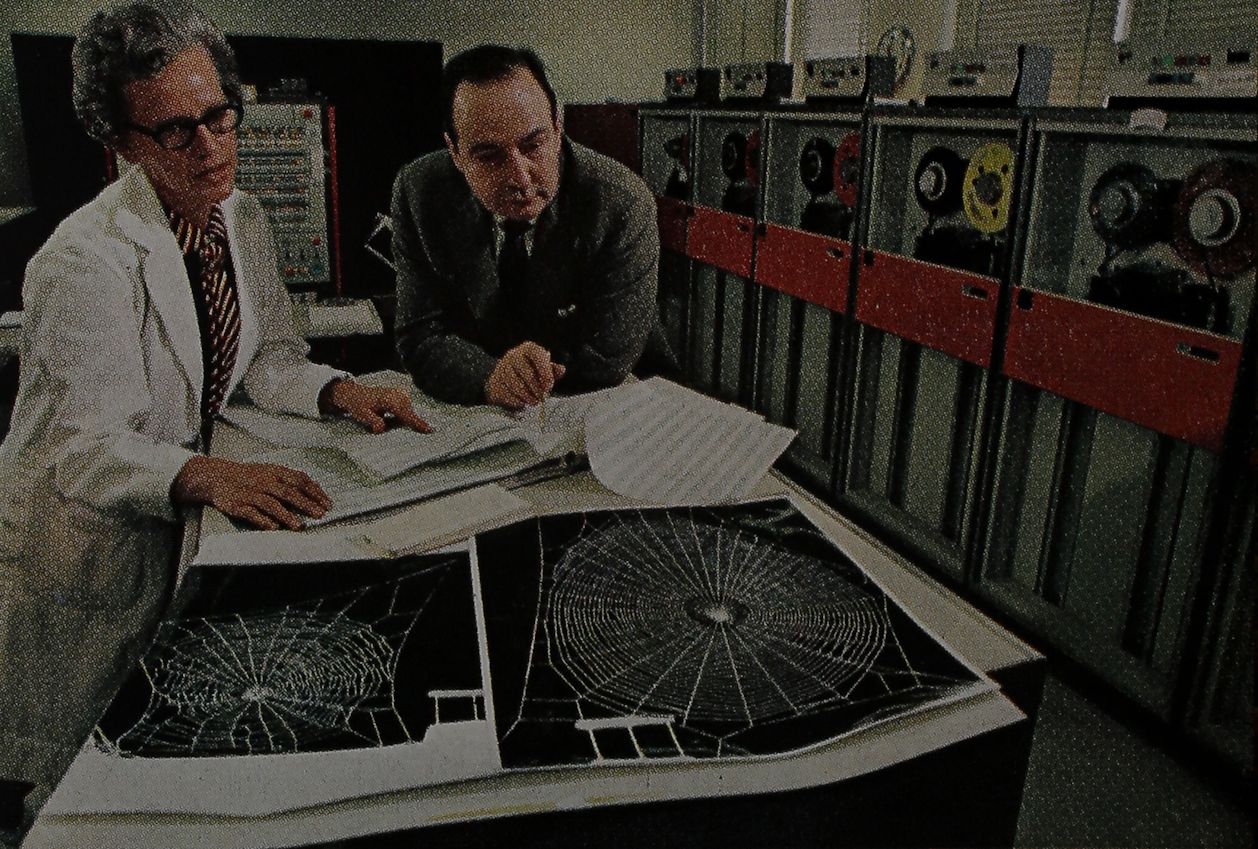

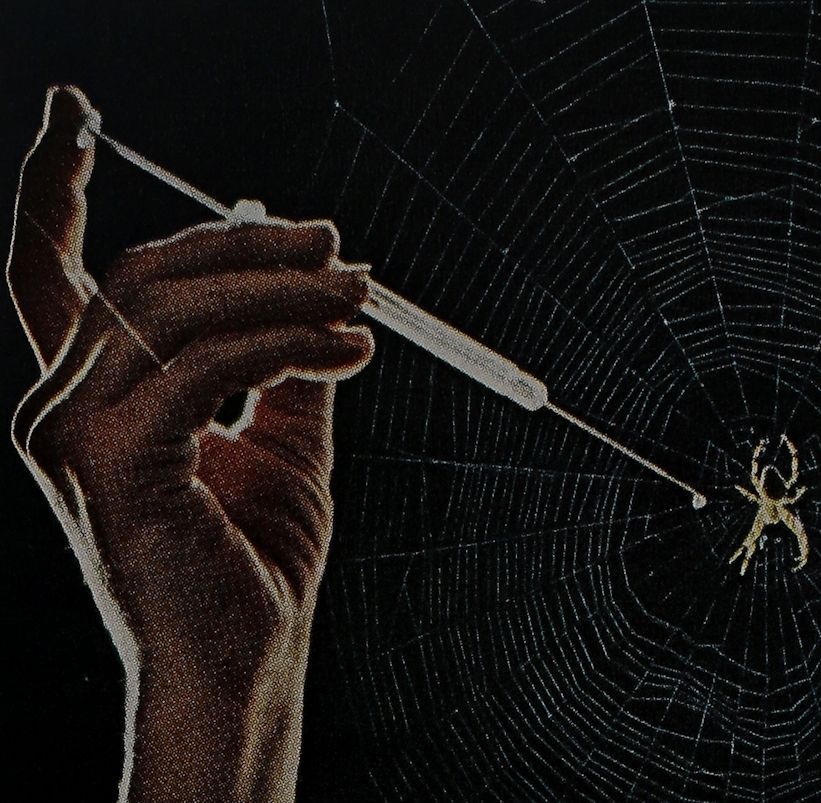

Drug trips for science:

weavers perform in thmaB%atory .

of the North Carolina Department

of Meri||t Health at Raleigh. Re-

search Director Dr. Peter

and his associates permit a spider

to

(lefte T|teñ Hjii$ apply a drop of

“spe@i|—the stftnulant dexedriné

sulphate—to the ^creatúre’s mouth

(right) Allowed.* to huiid another ..

web’íléenter^ an tÉif»lflÍ

irregular copy.p?aking information

from . pirotib|g^^

dexedrine-ipfluenced webs (bottom^

D® iW itt

‘»;fi^b®])uter Kjk compares .6(©©(1se-

. Such research revislÉ thaMeaeh

|fttug’ ■

characteristic changes in a spider’s

web-weaMjng activity AaÄeM

feirregular wilmä tranquilizers , and ■.

maiiiteáná^^^ll affifpS áñfiBiD,

more symmetrical webs—apparent-

ly because the druggeflipider is less

, Mstracted by Outside influentes.

By observing thi’ieffects ,q| drugs ^

:on spiders, .scientists :hf#i^|^litearn

more aboM -human biochemistry.

attachments, all engineered with mathemati-

cal precision.

Another spider of the same species was busy

spinning in a duplicate frame alongside. Ear-

lier, this spider had demonstrated its ability

to weave a regular, symmetric^ web. Split

now it had been fed a droplet of sugar water

containing “speed”—dexedrin© ililphai^S

Mrs. Scarbpro sprayed the two webs with

quick-drying white paint to make the threads

“”-stand out clearly. T1§||H saw^the^ stpSrge

angles and illogical backtrackings in the

weaving of the drugged spider. Laboratory

measurements would record angles, affixment

points, number of spokes, and other data for

computer analysis.

Experimenters have found that different

drugs—caffeine, mescaline, and LSD, for

example—produce characteristic variations

¡¡¡¡nm spider’sftwej||l|

SomeA-nUmám^m seem^toí be

accompanied by biochemical changes in the

blood or tissue fluids. Could such fluids, ad-

ministered to a spider,|||asurably infliu-me,|

its

perhapsiÄ^Be ter tell us—through the vary-

ing pattern^ of their webiSthe particular

illness affecting a patient, or even his progress

under psychiatric treatment. This is only one

potential of the experiments, which are still

in expMp|||iy-stag^S

Spider Responds to Strange, Vibrations

Researchers are on more certain ground in

the field of normal spider behavior. Dr. Peter

N. Witt, distinguished research pharmacolo-

gist and director of spider investigations at

the North Carolina laboratory, repeated an

experiment for me.

He tapped a tuning fork and touched it

gently to a web tended by an Argiope. In-

stantly she rushed across the strands and

furiously assaulted the quivering metal. With

her legs she pulled a silken stream from her

spinnerets, and in. seconds the cold prongs

were bound tight.

“A slave to innate behavior patterns,” said

Dr. Witt. “Spiders can’t alter their reactions,

can’t discern or evaluate subtle changes in

external influences. The vibration of a tuning j

fork or a thrashing insect—it’s all the same I

fhem.Hj

Perhaps even more instinct-bound than the I

orb-web spiders are two enemies I encounB

tered while spider hunting with young Nicho-1

las Eltz, who was then helping scientists atl

th||American Museum of Natural History’s®

Southwestern Research Station near Portal, I

Arizona. Nicky’s terrariums already held afl

Mjfzen tarantSlits,

Battle’s Outcome Rarely Varies

-The sif^Bagii set and%he desert was losing®

its daytime heat as I drove slowly down a I

twisting roadway across rolling terrai»

■’ covered with sage and cactus. Nicky perched*

on the hood, a flashlight in one hand and a I

wide-mouthed jar in the other. He had ex-1

|[[Hlné(f¡j|Hfy’ atMusk in summer tarantulas I

«j¡|velpéir ho¡|¡¡ to fdrage or to find mates*

“After dark it’s cooler, and they’re also safe I

from pompilid wasps,”

Abrújltly, Nicky -signaled, me ttjstop. He I

jumped off the hood* ran ahead, and suddenly®

to H® knees on the macadam. In the

headlight glare I saw him scoop up something I

with his collecting jar. A moment later he I

was back with his prize-^a tarantula with a I

body thicker than my thumb, a leg spread of ■

five indjOfeand two formidable black fangs. I

We ’Ragged six mhpjÉ specimens’ within anl

hour, then returned to the research station.

Earlier that day we had netted a metallic- 1

blue, topaz-winged pompilid wasp and re- 1

leased it in a glass terrarium partly filled with 1

desert sand. Now we dumped one of our new- I

ly captured tarantulas in with the wasp.

“First they’ll wrestle,” Nicky predicted, I

“but the outcome is usually the same.”

I watched the unequal struggle, the keen- I

eyed wasp circling like a gladiator and sizing I

up the near-sighted spider, which could as- I

sume only a threatening attitude until touched. I

The wasp quickly broke through the spider’s I

guard. With a lightning-swift jab, she sank I

her stinger into the tarantula between its I

third and fourth leg sockets.

Nimble crab spider haunts a

plant laden with delicate blosl

soms (right?). Named for its

ability taf* scurry sideways and

backwards, the little hunter can

turn white, pink, or yellow to

blend with vegetation.

In a mini-jungle of stalks and

stems, a green lynx spider snatch-

es up a victim. It trails a dragl

line—a safety thread anchored at

intervals—that most spiders put

down as they move about.

PEUCETIA VIRIDANS, 2 l/4 TIMES LIFE-SIZE, XYSTMlfslG^ISTMCTM 3^MES l$|$E-S|Z;E, ^ROPE:

S0UTHERbYuJAme™AnV,™Í¿ardEkÉrn Ready-for-dinner stance: A hungry crab spider waits ■

motionless for a flying insect to approach. When a

victim draws near enough, the legs snap shut and the

predator delivers a killing bite. Equipped with par-

ticularly potent toxin, these spiders readily attack

wasps and bumblebees much larger than themselves.

dark places nearly every-

where’ in |#^g^l|if§ed cellar

fojuml^This one (left)

BjH than most species, cellar

: ‘^áÉ^fc their webs will. niallsj ■’

■ lajE^Byj« iftt^

11olding recently hatched young.

violently

v^^teíth’é^p^ebs when alarmed, but

*\\ hr i«iff-,i’t eás ¿hey :

i I’l^jPjr^^^-lu^Tii kname

relatives, the harvestmen (page 211).

-1I¡É her preÉ||i^“to-be

■WEfeMH^Pv-1 mEh^MP^wm Sj^tder

(above). Crouched defiantly «| her

iipmaM^K. every as

HHBfflKj?.. This

‘ Zahl slit the co-

edon with scissors té expose the eggs.

Usuall-yr;: hd^ever, the crab spider dies

of old age before her babies emerge.

For a seconds me wasp held her

de|»f. thrust, apparently discharging a full

Sd’se^of tra®piffizep Then she withdrew’her

steppfd!^’flbac%|. and

, waited. The trán^Mize r worked rapidly.

ij«iii^^B«i^wpss iillrier was tenstimes the

wasp;seized- onedfl

l|pe tarantula’s legs in her jaws and tuggedl

the gray-black hulk across the sand to a hole]

she had dug eapler, SÄ hacked dc^Mt|^

h»,’pS§ÉJ h^iitrdi^in after her.

fpl already ktoteJW the last act of Jpis drama. 1

back – unmer-1

ground, the wasp would lay a single eggMnl

the anesthetized spider’s abdomen, «lia

return to the surface and plug the hole witM

sand or pebbles. The tarantula is thus literally i

buried alive for weeks. When the wasp’s egg.]

hatches into a squirming larva, the spider]

serves as |a food supply. This small, savagel

iritual helps control the tarantula population

—a necessity even with a creature so s||plN

i harmful li

Even the noiOrious:liackj^MI^^ f.mtrn-

\ dectus, of world-girdling rangé| accounts Ifpr

‘ surprisingly few Shuman fatalities. Of 1,000

■ cases of black-^dowmiite llfepiiried^Éh^re

United States each year, SSwos five are •

I fatal. ‘• Black-Wlllw’ venfeia^pSf \IÄÄ: ‘ghi

I antivenin was developed 25 -years ago~cani

produce such symjatems asy cMlls, n^&sea,

pain, hypertension, breathing^Séui^lifl and

Imuscle cft^pi^S

Trash Heaps AreHo»e:t0;;^p^^?f|i^ws

I In the company of Lorin Honetschlager, an

I animal collector wh|> some y|#fs parlier »ad’

1 helped file find seorp»ns,* I learnea^aMÍrst-

\ hand much of what I know of filack wi$pyys….

■.Last summer.- iitffeng’B 1pí^^pft|ni|0ÍHHfe ¿

lubuflÄ^lloiae mear Phoenix, Arizona, Lorin

lauifti.-.^in^ t^i Ié» I thought Latro-

dee’tm was a scarce spiqfer. “Widows?” he

minutes I’ll shcwj|§u hundreds.”

– We walked down the street to the backyard

of an abandonedKihouse where a trash heap

Ä»i^wäste paper’, tin

cans, and r@fii®tg^U«lier, we found a tangle

central

tube-shaped netting harboring a shiny black

eight-legger with’a pea-size abdomen marked

underneath with the scarlet figure of an hour-

■fglasstoages 192rt3|É|

World and

powerful poison^

• will ‘bite. ||fhriri ^Maiíid, only

¡when IjxééSsiylp pgé&he’d—that at, when

*See in National Geographic!, “Scorpions: Living

the Sands,haul Á, Zähl, March 1968. ;

Prickly “face” scowls from the back of a

humped orb weaver. Many spiders display

such elaborate markings. “Eyes” and “nos-

trils” in this bird’s-eye view actually indicate

the attachment points of internal muscles. The

spider’s legs conceal the real face.

GENUS ARANEUS, 9 l/2 TIMES LIFE-SIZE, NORTHERN HEMISPHERE;

BY PAUL A&gAHL © N.G.S.

Hidden in full view, a drab ogre-faced spi-

der avoids enemies by simulating vegetation

(right). It maintains the twiglike position—|

long legs stretched out fore and aft—while

it sleeps away the day. At night it awakens

to hunt for food.

DINOPIS SPINOSUS, I 3/4 TIMES LIFE-SIZE, SOUTHEASTERN U. S.;l

BY JAMES AND RICHARD KERflf

Life-saving ||||micry protects this jumping

. Slider ants distaste-

ful. M®t i^fejmitatilg spiders even copy the

” movements of tWt models, ^»•il’i’cn waving

anife^d^i When disturbed,

^^»|ver, they abandon pretehse and flee.

Spiders’ look-alike kin, the harvestman—or

lladdy loftglegs—has only two eyes, usually

mounted atop a short, round body. Able to

regenerate legs, it readily sheds them when in

¡danger of capture; this one has lost two.

Blotched costume conceals a cryptic bark

spider as it stalks down a lichen-covered tree.

Where polluted air has blackened tree trunks,

darker spiders have evolved.

Lurking lady of the meadows

(top left), this shamrock spider

normally stays hidden in a re-

treat of folded leaves positioned

near her 2V2-foot-wide orb web.

A taut trapline links hideout

and snare. When an insect

strikes, the trapline transmits

the vibrations of its struggle

from the web to the spider, who

rushes in for the kill.

Pear-shaped and berry-bright,

this Jamaican orb weaver

(above) displays apparel befit-

ting its tropical habitat.

uncomfortably unmernfnW

squeezed, or when^^^’|3^^^Eoleri”fl^E|S

turbed. With long chrome tweezers we picked

iff a |pz;eh|if the¿dÍB^^deladip^Vfe^^^E

silken egg cases shaped like little marbles,

Imp s^eral 3at$^

are and pose no Kiip^ph’a^

Back ffifthe laboratory I had improvised in

qhap-

pened. As I was traifáferring the black widojffl

her

ni^‘i1 < 1 up my

Wtm to the eltói^^pS|ié^^^^^^^Mwv¿’Uí-;

vey this new world of h

^fcir^i eay||wEw.iK’^^^HW 1 ejl^I^H frpm

comfortable.

»Trying not to move my right arm,

ly reached with ffoggHftpen jar on

a nearby shelf.

who Slid, if she chose, bite me at any mo-

ment. Maneuvering ever so carefully, J gently

^axed the venomous creature baflvfiH^E^

ri ty^;th^|,r.

Bp|n ‘’Stjio vy;ii~7Unic‘«i

pet upon and imme*dMijS killed .theffi^ivjS

moths, and other insects I dropped ihto her

npiliam; The action seemed just as bmi^H

purposefulS the prb-^^pi<m^®E^^™

^Kbrating tuning fork. The widouli^^^S

pertly twirled her victims into silken shrouds

■¡■g them .wjjjjRy- he ä t l^i^

visions for tWéafiuMa^^B

Gleaming Eyes Betray Prowling Wolves

I drove o.ut^^n

the desert east of «fe^É||Wthe habifaj of

A mem-

Epr of the)>hunting group,1 tiling cfqútug¿

|||fes-. he1i’)\Sul^iHlÉliÍÉ

sand, bits of bark, twigs, leaf fragment)

and grass.

Hffl»Rig no use whatever of the web-snare

and night,

^stimoving wolf spiders stre.äk;^^^| .¿the

ground in pursuit ,We found them-

easily, ¡íty?f¡ in their

«pbhs tgJów<edJM the headii^feWl’Sny ^autoj

mobiles, and glare they

B§Med■ to freeze in

One sp^^ÄM^^opean wolf spider,

^^^^^tarentui^y pvo^^^^^d

^^na^city^f^Taranto, popular

[folk danc|. It wps once thought that the effect

SpMl|Ä hfl#;.->f^Äll||f not serious)

jppuld be shaken off by dancing wildly, hence

:ll^biMte<ii^^^^pi )l NnitPihaRmiyBM

IS-name,

African tarant«|H

j^&ihother

^{^aBamily AseleMl^^wlh^ novel traH

■At^|]|^entranany cranny ^she

^^MÍ^’a^Mhd”\bf^tarbauliñ,:^i>’‘ a céh’trah

funnel-like onening^w^^hM^Min wait.

p$3|n| the bac’kyaMiof my home in Wasn^ffl

ton, D. C., stands a wall of unmortared

H||||in ^^^H^.spid^^pvfijthis family li^

uiwi T

thenr,jfe|Si^r. toll of harmful

garden .^^^^piust faMgs. .Many &

summer evening after dark I have placed a

chair feet fj^iÄe wall and, with

lili» farra session of’;

spider watching. ..

Playing Catch With a Hungry Spider

v©h.é‘‘-‘mght I came with food—live insects

«ÉeáyehirilBtri n-.*l l@{Smwre bham Of my

■flashfpih|^|)únd the mqutMf a funnel whet|fi

■ÉlSl ilÉlyl^fe^^and tense, sat a gráyi®|

spider with ceHmHHH^^Vhen I made

a sudden ’md^vfogwaÉd^ with ffiq flashlight,;

ogs^ror a second

&fi two. ^wa^tied until l|R^|^SggH was.

¿’lftaara- jtlfen^itjq^eaa a fly

^e’b fiHm^É»^ffir»»Éi^áÍTOches

from |he- fifcÉÉéfcM

streaked from ambu^h,T®§Ée the catch, and

^.i^fahea^fflflhack info the funnel. .

Many hunting^^d^rs^have large, efficient

are the

jumping spide^|f^|lÄalticidae). Although

í^sualí^ quiteS small ahJ|^har.m,l^^;o man,

atnp^riolíliVjMilored ÉÉlWrs leap upon insects

SA^S^@Ri^aLrer-\ j qfóleqpards. ‘$. species of

|¡iímpeF^BP)e’feh fou^^^^MKeet up on

Mount »EÄothe?s’ Infjmwland gar-

plths and wild wqq;i^|áÉ

Several of the hunti^Éfeaic ants in’ agN|

pear anee and habit (page 21 wome can buzz

like bees^^B^quirt out a viscous substance

‘fe entangleprey.

One of the, st’g^dges^qfj»^ hunters, the

jfefeáSjsffipider (Dolóme d$s),Jk. at home in two

HHg^Épaiez^JBl^nly can the fishing qpider

run across ,wa¡f>É^^S^ may remain |l|B

&ii^ifefor as lpng as^an hour,Mlding onto

bottom debris in quie’t streams mid ponil.^ ^

*Tkis remarkable f§at by sQ^pé an(f aquatic

insects was dps^fibed in “Teeming Life of a Pond,” by

WiltÉglH. Amos, National GEóGiuvpmc,%^^b|^®¿

Misstep 35,000,000 years ago mired this jumping spider

in resin, which hardened tt«amber. The oldest fossil spi£jS

der predates him by more than 315;0,@0,0@0 years.

Nemesis of smaller creatures. »Ine, wolfífepider

rarely threatens humans; if handled carefully, the hunter

can make an interesting pet.

For spider collectors who want nonliving specimens,

nature provides plentiful and perfect facsimiles such as

this featherlight exoskeleton (below) abandoned by the-

animal when it molted. Spiders must discard their skins to

grow, andjpthey do||||at least once even before emerging

from their egg sacs. lljllr to Ä|||ti times in all,

reaching sexual maturity final Few

spiders live more than two years, and the males, who dié^*

soon after mating, rareKy surviye.

Peekaboo predator scouts for food fro©fo}the

entrance of her underground home (above). If an

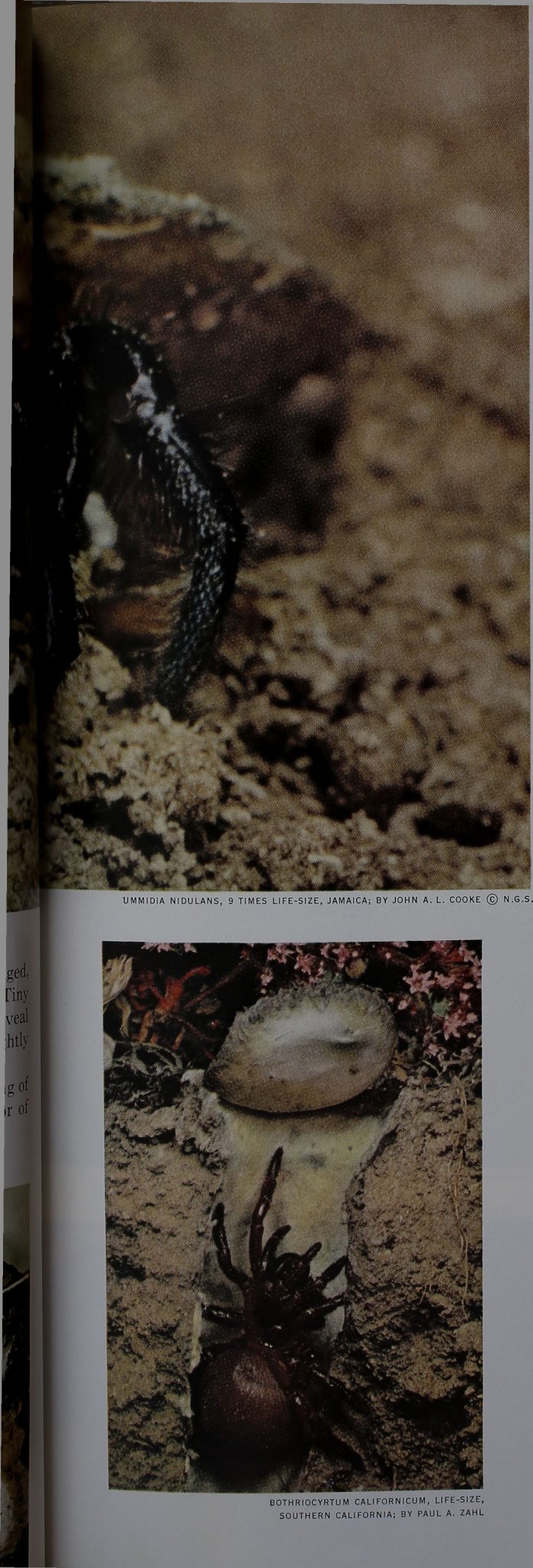

insect passes near enough, the trap-door spider

will lunge at it, usually keeping the door propped

open with her back legs to ensure a safé retrc’áíff’

Using comblike rakes on the jaws, the builder of

a trap-door nest such as the one being probed byS

Kathy Wilson Rottschafer (below) digs a hole

five to eight inches deep, then caps it with a hinged,

beveled door carefully camouflaged on top. Tiny

punctures on the inside of the door (below) reveal

h|3W>’the spider uses her fangs to hold it tightly

shut against intruders.

After waterproofing the walls with a coating of

I®»? Wl***.’ tb* spider lines the interior of

with soft silk (opposite).

A bubble of air held under the body enables

’ ’it to^piop;;||^the surfabÉ at ijidll. Insects are

its usual prey, but some species capture

small fish and tadpoles (page 203).

Even more remarkable, the water spider

Argyroneta—a native of Europe and Asia^^f

builds a diving bell underwater. The spider

first spins a submerged web platform, then

carries down small hir bubbles from||he sur-

face to fill it like a tiny balloon. She spends

virtually her entire life in or near the bell,

adding new air whenever needed. Argyroneta

even lays her eggs within the bubble, and

hatchlings stay there [»til ready to set ©(ut

IS^lagir own. ‘

Camouflage Hides a Hunter’s Lair

Trap-door spiders are unique by virtue of

their ingenious dwellings. One spring I found

myself in the hilly country east of San Diego,

a haunt of the Cali-

fornia trap-door Bothriocyrtum californicum.

Here my field collaborator was Kathy Wilson

Rottschafer, a student of biology at San Diego

State College, and a trap-door specialist in

[R making.

“When they’re closed, the traps are so per-

fectly camouflage® that we’ve probably

stepped on dozens already without knowing

it,” apologized Kathy. We were searching a

little.arro1v<| strewn with yellow spring flow-

ers. Here and there lay patches of bare earth

where, onejeould examine the surface square

inch by square inch.

For ten minutes ffl scrutinized the ground,

^Eskin-g fo’l isomething j had previously seen

only in photos, ffl’hen I heard a cry of triumph

.frpitaa Kathy^gfeg pointed .to a hair-thin ire

barely visible on the surface of the soil,

fflpffay ^^feyb^^our pocke;£knife, .please?”

■ ihe asked. With a surgeon’s dexterity she

eased the blade ulper the edge of the inch-

wide door and pried gently. There was no give.

“A’ spider’s in’ ‘there, all right,” she said,

i *Sd jija&t under the door, holding it shut.

Surprising how strong they are.”

She thumped the ground gently and the spi-

der let go. With the blade she lifted the trap-

door—a thick cap of tightly compacted silk

and dry soil. Its beveled edges might have

been fashioned on a lathe (left).

The young arachnologist beamed. “There

you are. And six or eight inches down at the

-bottom of the shaft is the lady of the house.”

With sharp rakes on each of its two jaws,

the spider had excavated a neat vertical shaft

just wide enough for her body; she had coated

its walls with saliva-moistened earth, and

covered them with a sheet of tightly spun silk.

Finally she had woven the hinged and cam-

ouflaged trapdoor—her shield against a

hostile world.

She was now safe from most of her enemies

but still vulnerable to the pompilid wasp—

nemesis of all members of the tarantula grpup.

When such a %a$p locates a trapdwr-, it

chews through the cap or simply rushes in

if the spider lifts the door too high. Once in-

side, the wasp engages the spider in the same

unequal contest I had observed against the

tarantula in Arizona. Then the insect departs

through the now-unguarded door.

The trap-door spider designs her abode not

only for safety, but also as a shelter from sun,

rain, and tt^p^iis her parlc^haóra

her nuptial chamber, and a nursery for her

young. Seldom if ever does she leave its con-

fines, and even then ventures out only a few

inches to capture crawling insects.

Indians Believed in Spider Power

Greek mythology gave us Arachne. Other

myths deify the spider. “To the American In-

dians,” writes Dr. Gertsch, “the Spider is a

creature of

Dakotas “the orb web is a symbol of the heav-

ens … from the spirals of the orb emanate

the mystery an#power of thfei, Great SpirlÄ

And the lines connect sky and earth on which

an “… Algonkin maiden, fallen from grace

as wife of the Morning Star, is sent back to

earth.” To certain Southwest Indians, the

original creator was a spider; to others, weav-

ing was introduced by a spider woman.

Quaint myths. But where do spiders fit into

nature’s plan, and into the World which man

has superimposed on nature?

To begin with, the arachnid line goes back

400 million years to the first land-dwelling

invertebrates. Ages of adaptation followed,

during which spiders infiltrated almost every

climate and every ecological niche.

Housewives are aware that any closet or

dark corner, even on the thirtieth floor of 1

a New York apartment building, if left un- i

swept or undusted for just a few weeks, will

inevitably develop cobwebs. How they get ]

¡flere strains one’s imagination.

Gossamer Webs Capture Morning’s Glory

ffit only are spiders found almost every-

where; they exist in incalculable numbers. ¡

Sampling techniques have revealed some

64,000 spiders in one acre of meadow in a :

Middle Atlantic state and a quarter of a mil-

lion in an acre of tropical forest. The world-

wide count would be beyond comprehension.

Tfee spider’s marvelously inventive modes :

are fueled by strictly carnivorous habits

which, although deadly in the insect world,

are man’s distinct blessing. Man must live

on what he grows, and thanks in part to

his eight-legged friends, destructive insects

are held in check. It seems ironic that such a

benefactor should typify ugliness and con-

note menace—should have, as the nursery

rhyme has it, “frightened Miss Muffet away.”

Early one September morning on a New

England hillside, I came upon a patch of

mountain laurel in which scores of orb webs j

»ere strung. Their silken fibers, moist with

dew, caught the rays of the rising sun, and

|m| glitter was dazzling (page 197).

Perhaps a similar enchanting encounter in

1715 inspired 12-year-old Jonathan Edwards,

the future Puritan theologian and scholar, to

pen ;what I think of as the best tribute to

man’s plentiful eight-legged friends. (Edwards

could not have known that a century later

scientists would decide that spiders are not |

‘ insects.) ■

“… every thing belonging to this inspf’’ 1

wrote EdwardÉ “is a^piÉjffle….”